In This Chapter

- Using the natural aids when you ride

- Asking a horse to walk

- Positioning yourself for Western, hunt seat, and dressage walking

- Stopping, turning, circling, and backing

- Practicing new skills with some exercises

As a new rider, the first gait

you master is the walk. Because the walk is the slowest gait, you have more

time to think about the cues you’re giving the horse. How convenient! It’s the

easiest gait to ride and the one you’ll use the most, especially if you plan to

trail ride.

The walk is a gentle,

rocking gait that’s easy on your seat. When a horse walks, his legs move in the

following order: left rear, left front, right rear, right front. Three legs are

on the ground pretty much at the same time (see Chapter Head

to Hoof: The Mind and Mechanics of a Horse for a figure showing

the walk). Most horses walk at about 4 miles per hour.

In this chapter, I tell you what

you need to know to ask the horse to walk. You discover how to ride the walk in

the Western and English disciplines as well as how to make the horse change

directions, move backward, circle, and stop. At the end of the chapter, you

find exercises you can try to build your riding skills at the walk. But to

start you off, I describe the natural aids that horseback riders use when they

ride all gaits.

Remember

When riding the walk in any discipline, maintaining correct position with your body, hands, and legs is important. Keeping the proper equitation, as people call it, helps you stay balanced and communicate more effectively with the horse. Your riding instructor can help you with this and everything else mentioned in this chapter.

Body Language: Helping Your Riding with the Natural Aids

The walk is the first gait where

you hear about the natural aids. The natural aids, which are your

primary tools when riding a horse, include the following:

- Hands

- Legs

- Seat

- Voice

As I explain in the following

sections, you use the natural aids to let the horse know what you want him to

do. As you read through this chapter and Chapters Bumping

Up Your Skills with the Jog or Trot and Getting

on the Fast Track with the Lope or Canter, you can see many

references to using your hands, legs, seat, and voice. These natural aids are

an integral part of your riding. (For info on artificial aids, see Chapter Equipping

Yourself with Other Important Gear.)

Your hands

A very important means of

communication is your hands. Your hands hold a direct connection to the horse’s

mouth via the reins and bit. The way you use your hands determines how well you

send signals to the front part of your horse. These signals help communicate

direction and speed. In more advanced riding, the hands may communicate more-complex

messages.

The discipline you ride in

determines how much contact your hands should have with your horse’s mouth. In

dressage, for example, you keep a fairly taut (but not tight) rein that enables

you to have direct contact with the bit. In Western, your reins should have a

little more slack unless you’re stopping the horse.

Your legs

Your legs are a crucial

instrument among your riding communication tools. They cue the horse in a

number of different ways, indicating things such as speed and direction. In

essence, your legs control the horse’s hind end.

Your seat

The seat is a vital but sometimes

overlooked natural aid in communicating with the horse. Basically, your seat

is your weight and the way you shift it in the saddle. Although this

natural aid can be tricky for beginning riders to understand at first, you need

to know how to use your seat effectively when you ride.

Remember

Riders in the various disciplines use their seats differently. Dressage riders use their seats to cue their horses to perform a variety of maneuvers; riders in some Western disciplines use their seats to keep their horses at a slow, steady pace. All riders use their seats to slow their horses to a stop, which makes the seat a particularly important tool.

Your voice

Voice is the aid that’s easiest

for novice riders to master. Through your words and tone of voice, you can

communicate a number of messages to the horse, including how fast you want to

go (slow or fast) and praise or correction.

Riders in all disciplines use

voice when working with their horses. Dressage riders aren’t allowed to use

voice in competition, so many avoid it when training so they don’t get into the

habit of using it. Trail riders, however, use voice quite a bit to reassure a

horse who sees something he finds scary on the trail.

Asking a Horse to Go for a Walk

Your first task if you want to

ride a horse at the walk is to cue him forward. The way you cue him varies

according to discipline, although the differences are subtle.

Tip

Each horse is different, and some are more responsive than others. You may find that your cues to ask one horse to walk may need to be “louder” than the same cue on another horse. The rule of thumb is to ask quietly first and increase the volume (intensity) if you don’t get a response.

As I describe how to get a horse

to walk forward in the following sections, I assume you’ve just gotten on and are

at a stop. Chapter Mounting

and Dismounting outlines the steps for mounting a horse.

Western cues

When riding Western, you ask a

horse to walk by gently squeezing the horse’s sides with your calves (keeping

your knees in place). Maintain this pressure until the horse moves forward.

After you feel the horse respond, relax your calves.

Tip

If the horse doesn’t respond at first, increase the pressure until you get a response. You may need to use your voice to encourage the horse to go. For horses, clucking with your tongue is a fairly universal signal to move forward.

When asking the horse to go

forward, be sure your reins are somewhat slack. Keep your body position in mind

as the horse starts to move forward. I describe correct Western body position

at the walk later in this chapter.

English requests

English riders ask a horse to

walk by using leg pressure. Squeeze the horse forward with your calves (not

your knees) by pressing in on his sides and maintain this pressure until the

horse moves forward. After the horse responds, relax your calves. Be careful

not to take your calves completely off the horse, because you want to maintain

some contact with your legs.

When asking the horse to walk

when riding hunt seat, your reins should be neither too tight nor too slack.

Traditionally, you want to keep a straight line in the reins from bit to elbow.

If you’re riding dressage, you should have some contact with the bit, which

means you have slight tension in your reins.

In hunt seat riding — but not in

dressage — you can also use your voice to encourage the horse to go forward if

you don’t get an immediate response to your leg pressure. You do this by

clucking.

Riding the Walk in Western

In Western riding, the walk is a

slow, easy gait that’s comfortable to ride for long periods of time. Because

the Western discipline is the one most commonly used for trail riding (see

Chapter Don’t

Fence Me In: Trail Riding), the walk is the gait that Western riders use most often.

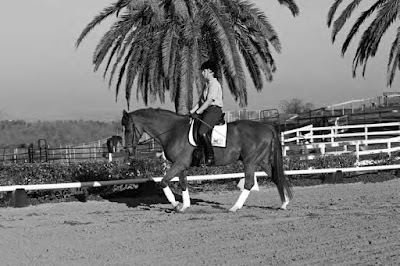

When you’re in correct position,

your body is relaxed, the reins are about 2 inches above the horse’s withers,

and the balls of your feet are squarely in the stirrups. Figure 13-1 shows a

Western rider at the walk. Read the following sections for details on how to

position yourself correctly. See Chapter Head

to Hoof: The Mind and Mechanics of a Horse for info on horse anatomy; Chapter Dressing

Up Horses with Saddles includes images of saddles.

Figure 13-1: Stay relaxed when

you ride the walk in Western.

Positioning your body

Remember

Relaxation is key when riding Western; however, you do need to keep yourself in the proper position without being stiff or unnatural. Here’s what that position entails (refer back to Figure 13-1):

- When riding Western, remember to “sit deep.” This phrase means that your weight is on your seat bones. Relaxing your pelvis and lower back can help you achieve a deep seat.

- Sit up straight, but don’t sit like you have a board in your back. Your shoulders should be relaxed but not slumped forward.

Tip: To help get a sense of where your shoulders should be, take a deep breath and exhale. Keep your shoulders in the position they land in when you let the air out.

- Make sure you aren’t leaning to one side of the horse or another. In other words, sit square in the saddle. Use the saddle horn as a guide to make sure you’re centered. The horn should be directly in front of you if you’re in the right spot.

- Keep your elbows relaxed but at your sides. Avoid a common pitfall of beginners: letting your elbows stick out like you’re about to imitate a chicken!

- Don’t forget your head. Many beginners have a tendency to stare at their horse’s ears. To maintain your balance, keep your chin up and your eyes directed at where you’re going.

Trying your hand at holding the reins

Western riders have two different

ways of holding the reins. These styles originated in different parts of the

country, and riders usually prefer one style over another. I explain both

styles to you, but the one you use will most likely depend on what your riding

instructor prefers:

- California: Because I grew up in Southern California, I learned to ride Western using the California style of holding the reins. This style is common in many parts of the Western United States.

California requires that you hold the reins in the left hand. The reins come up through the bottom of your hand, with one rein going up between your pinky and your ring finger and the other rein pressed against your palm. Your thumb should be on the top of the reins facing upward (see Figure 13-2).

- Traditional: Riders in many parts of the country hold the reins traditional style, which means they use either their right or left hand. You hold one rein between the thumb and the index finger and the other between the index finger and the middle finger. The thumbnail faces upward and the thumb points toward the horse’s neck. The reins exit your hand between your pinky and palm (see Figure 13-3).

Figure 13-2: In California

style, hold the reins in your left hand with your thumb facing up.

Figure 13-3: In

traditional style, hold the reins between fingers with your thumb pointed toward

the horse’s neck.

In both styles, you hold the

reins about 2 inches above the horse’s withers (see Chapter Head

to Hoof: The Mind and Mechanics of a Horse for a diagram of

the horse). Your hand should be in front of the saddle horn.

Tip

What about your other hand? In Western riding, you usually have the option of putting the unused hand on the same-side thigh or letting it hang alongside your leg, completely relaxed.

Putting your legs in position

Your stirrups are long when

riding Western, which is good if you plan to be in the saddle a long time.

Longer stirrups are easier on the knees.

When your horse is walking, you

should have the balls of your feet in the stirrup and your heels should be

down. Your toes should be pointed forward so your foot is parallel to the

horse’s body. If your stirrups are set at the correct length (your riding

instructor can help you with this), you should have a slight bend in your

knees, and your legs should go alongside the cinch. (Refer to back Figure 13-1

to see how to position your legs.)

Moving with the Western horse

As the horse walks, you feel his

motion beneath you. Tune in to this motion and feel its rhythm. See whether you

can sense how the horse’s left shoulder and then his right shoulder move. Feel

in sync with the rhythm as you let your body relax while still holding your

position. Let the horse’s movement gently rock your hips. If you get in tempo

with your horse, you should start to feel at one with the big creature beneath

you.

Riding the Walk in Hunt Seat

In hunt seat, the walk is the

gait you use primarily to warm up to the faster gaits. Horses whom people

choose for hunt seat riding often have big strides, making their walks feel

“bigger.” For this reason, the walk is a good gait for beginners to focus on.

Mastering this gait helps you develop balance and rhythm with the horse.

You should have a slightly

forward seat, your hands should be 2 to 3 inches apart, and your calves should

rest just behind the girth. Figure 13-4 depicts the proper alignment for riding

the walk in hunt seat; you can also check out the following sections to figure

out how to position yourself correctly. Chapters Head

to Hoof: The Mind and Mechanics of a Horse and Dressing

Up Horses with Saddles, respectively, can

show you figures of the parts of a horse and saddles.

Figure 13-4: A rider at the

walk in hunt seat is slightly forward.

Positioning your body

Remember

Hunt seat is a formal type of riding that requires a distinct position in the saddle. The challenge is to maintain the proper position while staying relaxed and moving freely with the horse (refer back to Figure 13-4):

- Your body position in hunt seat riding is slightly forward. This means you have a gentle bend at the hips (not the waist), which gives you a closed hip angle. Your weight in the saddle is on your seat bones.

- You have a slight, natural arch in your lower back, with the rest of your back flat. In other words, don’t force an arch or tuck in your pelvis.

- Your shoulders are squared and back rather than hunched forward.

- Your elbows are close to your body, your chin is up, and your eyes are lifted, looking ahead at where you’re going.

With both hands: Holding the reins

In hunt seat, you hold the reins

in two hands with your palms down. Have your fingers closed in a relaxed fist;

the reins go between your thumb and your index finger and exit the hand between

your pinky and ring fingers.

Hold your hands 2 to 3 inches

apart from each other, about 3 inches above the horse’s withers. Have the reins

relaxed but taut enough that someone looking at you from the side could draw a

straight line from the bit to your elbow (refer back to Figure 13-4).

Putting your legs in position

Tip

In hunt seat, your stirrups are fairly short, giving you a significant bend in your knee. To know what length your stirrups should be, take your feet out of your stirrups while you’re in the saddle. The bottom of the irons should rest at your ankle bone. If they come below it, they’re too long. Above it, they’re too short. Your riding instructor can help you determine whether your stirrup length is correct. If the stirrups are too short or too long, your instructor will adjust them for you or you’ll need to dismount to adjust them yourself.

When you’re in the saddle, your

calf should rest just behind the girth. The balls of your feet should be in the

stirrup, and your heels should be down. Let your weight rest on the balls of

your feet. Your toes should point forward at a slight outward angle of about 15

degrees. (Refer back to Figure 13-4.)

Tip

When the horse is walking, your knee should have contact with the saddle. A good way to judge how much pressure to apply is to imagine a sponge between the inside of your knee and the saddle. You want to keep the sponge in place without squeezing any water out of it.

Moving with the hunt-seat horse

When the horse is walking in hunt

seat, you need to keep your forward position. Move with the movement of the

horse while keeping your shoulders back and your hips relaxed. Feel the horse

move underneath you, allowing his movement to gently rock your hips back and

forth.

Remember

When the horse is moving, pay attention to your legs. Make sure they don’t slide forward or backward. They should stay just behind the girth.

Riding the Walk in Dressage

The walk is an important gait in

dressage, especially at the lower levels. If you intend to compete in dressage

in the future, you have to perform most maneuvers at this gait.

You should sit deep in the

saddle, your hands should be 2 inches above the horse’s withers, and your

calves should be about 1 inch behind the girth (see Chapter Head

to Hoof: The Mind and Mechanics of a Horse for images of the

parts of a horse, Chapter Dressing

Up Horses with Saddles for saddles). Figure 13-5 shows the proper position

for a dressage rider at the walk, and the following sections explain how to

position yourself correctly.

Figure 13-5: A dressage rider

at the walk sits deep in the saddle.

Positioning your body

Remember

Dressage riders use the following body position (refer back to Figure 13-5):

- In dressage, riders sit deep in the saddle. This means your weight drops down into your rear end. You sit on your seat bones and sink into your hips.

- Your shoulders are open and square yet relaxed.

- Your back is flat — you don’t want any arch.

- Your chin is up and your eyes are forward, looking where you’re going.

Get a grip: Holding the reins

In dressage, you hold the reins

in two hands, palms down. Your fingers are closed in a relaxed fist, and the

reins go between your thumb and your index finger and come out between your

pinky and ring fingers.

Your hands should be 3 to 4

inches apart, about 2 inches above the horse’s shoulders. You want slight

tension in your reins so you have contact with the horse’s mouth. (Refer back

to Figure 13-5.)

Putting your legs in position

When riding dressage, your

stirrups are longer than they’d be in hunt seat but shorter than in Western.

Your riding instructor can help you determine the correct stirrup length.

At the walk, your calf should be

about 1 inch behind the girth. Your heel should be in line with your hip, and

your knees should have considerable contact with the saddle without pinching

the horse. The balls of your feet are in the stirrups, and your heels are down.

Your toes point forward so your feet are parallel to the horse’s body. (See

Figure 13-5.)

Moving with the dressage horse

In dressage, riding should look

effortless. When the horse is in motion, your body should move with him as you

sit deep in the saddle.

Remember

Make sure your hips are relaxed and that you hold the body position described earlier in this chapter. The horse’s motion gently rocks your hips while the rest of your body stays where it should.

Maneuvering the Horse at the Walk

In the following sections, I describe a variety of helpful maneuvers at the walk. You want to be able to stop a horse after you’ve put him in motion (for info on how to start a horse, see the earlier section titled “Asking a Horse to Go for a Walk”). And unless you plan on riding in a straight line all the time, you need to know how to turn your horse and possibly move backward. Circling is another important skill you should develop on horseback, especially if you ever want to compete.

Pulling out all the stops

The stop is an important maneuver

that both horses and riders need to know well. Stopping is important in every

discipline because it gives the rider considerable control — and makes your

eventual dismount a bit less daunting!

A horse responds to specific

stopping cues depending on how he’s been trained, which differs slightly

between disciplines. I explain the cues in the following sections.

Western stops

For beginning riders, the stop

from the walk is a basic maneuver that you learn in the first lesson. To stop a

horse from a walk in Western riding, follow these steps (and see Figure 13-6):

1. Say “whoa” as you put

tension on the reins while moving your hand slowly backward toward your belly

button.

Remember

Keep in mind that when using a leverage bit (such a curb bit — see Chapter Getting a Heads-Up on Bridles for details), even the slightest pull on the reins puts considerable pressure on the horse’s mouth. For this reason, use your hands gently and carefully when riding with a leverage bit.

2. When the horse stops

walking, release the tension in the reins.

Figure 13-6: To stop a horse

in Western riding, say “whoa” as you put tension on the reins.

English stops

In hunt seat and dressage, you

request the stop in a manner similar to how you do it in Western (see the

preceding section), though you also use your weight to help bring the horse to

a halt. To stop a horse from a walk in English riding, follow these steps (see

Figure 13-7):

1. Sink your weight into the

saddle without slouching your shoulders and put more tension on the reins.

In hunt seat, put more tension on the reins while moving your hands backward and say “whoa.” In dressage, where you already have considerable contact (tension) on the reins, increase that tension. Do not use your voice; the horse should stop without your using this aid.

2. When the horse stops

walking, release the tension in the reins.

Figure 13-7: To stop a horse

in English riding, sink your weight into the saddle as you add tension to the

reins.

Turning left and right

Horses understand certain cues about

changing direction. The differences in cues are subtle, yet horses well-trained

in a particular riding discipline recognize these subtleties. Pay attention to

the directional cues for the discipline you plan to ride in. Although executing

these cues takes concentration at first, they’ll eventually become second

nature.

Remember

When first figuring out how to turn a horse, you start in an arena. The side of your horse next to the rail is called the outside, and the side away from the rail is called the inside. You need to know these terms because your riding instructor may make references to your outside leg, your inside leg, and in English riding, your inside rein and your outside rein.

Western turns

In Western riding, something

called neck reining is the most common way to turn a horse. Neck reining, or

cueing the horse to turn using rein pressure against the neck, can happen only

when you hold the reins in one hand (see “Trying your hand at holding the

reins,” earlier in this chapter). Still, don’t be surprised if you see Western

riders using what looks like an English bridle; when horses are first being

trained in Western riding, they learn the direct rein method, which is the same

method that English riders use at all levels.

Beginning riders usually pair up

with seasoned horses, so you’ll probably use neck reining. When riding Western,

turn your horse either to the left or right, using your reins and your legs, in

the following manner (see Figure 13-8):

1. To turn your horse to the

inside of the arena (away from the rail), move the hand holding the reins to

the inside so that the outside rein is lying across the horse’s neck; at the

same time, apply pressure with the calf of your outside leg.

The horse moves away from the pressure, encouraging him to turn to the inside.

2. When the turn is complete,

move your rein-hand back to the center of your horse and release the pressure

from your outside leg.

Figure 13-8: When turning

in Western riding, use neck reining to cue the horse.

English turns

In English riding, when you want

your horse to turn either to the left or right, use your reins and your legs in

the following manner (see Figure 13-9):

1. To turn your horse to the

inside of the arena (away from the rail), increase the tension on the inside

rein; at the same time, apply pressure with your outside leg.

If you’re riding hunt seat, pull the rein out slightly to the inside. If you’re riding dressage, pull the rein back slightly. The horse moves away from the leg pressure, which encourages him to turn to the inside.

2. When the turn is complete,

release the pressure on the inside rein and return it to its normal position;

release the pressure from your outside leg as well.

Figure 13-9: In English riding,

increase the tension on the inside rein when turning your horse.

Circling the horse

All novice riders find out how to

turn a horse in a large circle in their riding lessons. Circling is an

important maneuver because it helps you build both communication with your

horse and your riding skills.

Equestrians often use circling in

arena riding for a variety of reasons. In Western riding, circling is part of

reining competition. Hunt seat riders use the skills they develop through

circling when negotiating a jumping course. And in dressage competition,

circling is part of the tests at all levels.

The cues you use to circle a

horse depend on your riding discipline and the gait you’re using. The

differences are subtle, but a horse well-trained in a particular discipline

understands specific cues.

Western circling

When circling a horse at the walk

in Western riding, you neck rein (as I describe in the earlier section “Turning

left and right”), using one hand on the reins. The following steps take you

through a circle (see Figure 13-10):

1. Start riding straight along

the rail.

2. To turn to the inside (away

from the rail), move the hand holding the reins to the inside so that the

outside rein is lying across the horse’s neck; at the same time, apply pressure

with the calf of your outside leg.

The horse moves away from the pressure, which encourages him to turn to the inside.

3. Maintain the rein and leg

pressure as the horse turns.

When the horse is moving into the circle pattern, apply pressure with both legs to guide him through the circle.

4. When the circle is complete

(when you end up back where you started, on the rail), move your rein-hand back

to the center of your horse and release the pressure from your legs.

Figure 13-10: To circle in

Western riding, use neck reining and leg pressure.

English circling

When circling a horse at the walk

in hunt seat and dressage, you use direct reining, with two hands on the reins.

The following steps take you through a circle (see Figure 13-11):

1. Start riding straight along

the rail.

2. To circle your horse to the

inside of the arena, increase tension on the inside rein; at the same time,

apply pressure with your outside leg.

If you’re riding hunt seat, pull the rein out slightly. If you’re riding dressage, pull the rein back slightly. The horse moves away from the pressure of your leg, encouraging him to turn to the inside.

3. Continue to maintain the

rein and leg pressure as the horse turns.

When the horse is moving into a circle pattern, apply pressure with both legs to guide him through the circle.

4. When the circle is complete

(when you’re back on the rail), move your hands back to the center of your

horse.

Remember

Reduce the amount of pressure from your legs, but be sure not to take your legs off the horse completely. In both hunt seat and dressage, you need to maintain leg pressure to keep the horse moving forward — kind of like keeping your foot on the gas pedal!

Figure 13-11: To circle a horse

in English riding, put tension on the inside rein while applying pressure with

the outside leg.

In reverse: Calling for backup

Asking a horse to back up is a

simple task that everyone who wants to ride should master. In the show ring,

judges often ask for a back-up, and on the trail, backing up can become a

necessity.

As with most cues, the directions

for backing up differ slightly between disciplines, as you find out in the

following sections. Keep in mind that backing up is not a very natural maneuver

for the horse and thus requires some effort on his part.

Warning!

Always do the backup from a standstill, never from a walk or faster gait. Why? Because suddenly going into reverse while moving forward is too hard and confusing for a horse. You wouldn’t shift your car into reverse without first applying the brakes, right? For information on how to do that stop, see the earlier section called “Pulling out all the stops.”

Western

In Western riding, backing up is

particularly important. Roping-horses and horses working cattle in a ranch

environment use this maneuver. It’s also a vital movement for trail horses in

rough terrain. You never know when you’ll find yourself in a tight spot on the

trail and need to put the horse in reverse!

To back up your horse when riding

Western, follow these steps (also see Figure 13-12):

1. Slide your hand up the

reins toward the horse’s neck and create some tension in the reins.

Pull the reins gradually backward toward your belly button.

2. If the horse doesn’t start

to back up, apply pressure with both of your calves while maintaining backward

tension on the reins.

3. After the horse has taken

several steps backward (your situation determines how far back you want to go),

stop his movement by sending your hands forward toward his neck and releasing

leg pressure.

Figure 13-12: When backing

a horse in Western riding, slide your hand up the reins to create tension.

English

In the hunt seat discipline,

riders sometimes use backing up in the show ring, and both hunt seat and

dressage riders use it when out on the trail. Although not used as frequently

in the English disciplines as it is in Western riding, backing up is an

important maneuver that all English riders should know.

To back your horse when riding

English, follow these steps (and see Figure 13-13):

1. Gather up your reins a few

inches so you have less rein between your hands and the horse’s mouth.

Create some tension in the reins by pulling them back gradually toward your hips.

2. If the horse doesn’t start

to back up, alternately pull back gently on each rein.

If this movement doesn’t get a response, apply pressure with both of your calves while continuing to apply alternating tension on the reins.

3. After the horse has taken

several steps backward (your situation determines how far back you want to go),

stop his movement by sending your hands forward toward his neck and releasing

leg pressure.

Figure 13-13: To back up in

English riding, gather up your reins and create tension by pulling back gradually.

Trying a Couple of Walking Exercises

A good way to develop your riding

skills is to practice. Get on a horse and use the cues you’ve been taught. The

following sections describe some exercises to try. You can suggest these to

your riding instructor or do them when you’re riding on your own in an arena.

Using barrels in Western riding

A great walking exercise for Western riders uses barrels. The stable where you ride probably has barrels set up in the arena or may have them on the property and let you use them with permission. You can use poles if barrels aren’t available.

This exercise, which has you

weave in and out of the barrels, helps you both turn and circle your horse,

letting you develop the coordination you need between your rein-hand and your

legs (Figure 13-14 shows the pattern in which you should move):

1. Line up three barrels,

approximately 12 feet apart, in the center of the arena.

2. Start at one end of the

arena facing the barrels; walk the horse straight toward the barrels.

3. When you’re in front of the

first barrel, turn the horse slightly to the right and make a tight

counterclockwise circle around the barrel.

Walk all the way around till you’re facing the second barrel, and then walk straight.

4. Go to the next barrel and

turn your horse slightly to the left of that barrel so you can circle it

clockwise.

5. After completing your

circle, move on to the next barrel and circle counterclockwise.

6. When you’ve finished the

circle on this barrel, continue back to the middle barrel and circle it again.

Continue this routine back and forth through the barrels three times altogether.

Figure 13-14: In Western, use

barrels to practice turning and circling at the walk.

Figure 13-15 shows a rider

performing the exercise.

Figure 13-15: Practice going

around the barrels three times total.

Crazy eights: Turning a figure eight in English riding

The figure eight is a good

exercise for hunt seat and dressage riders to practice at the walk. It helps

you figure out how to turn and circle your horse, and it develops the

coordination you need between your legs and hands. You can do this exercise in

any riding arena (Figure 13-16 shows the pattern you want to make):

1. Start on the rail, and turn

your horse to the inside as though you were going to make a circle.

2. When you get halfway

through your circle, straighten your horse.

3. Ask the horse to change

directions to make a connecting circle in the opposite direction.

If your first circle was clockwise, the second will be counterclockwise.

4. After the horse completes

the circle, straighten him again and then begin a connecting circle in the

opposite direction.

Here, you’re completing the half-circle you made in Steps 1 and 2.

5. Continue walking through

this pattern four to six times.

Figure 13-16: In English, riding

a figure eight is a good way to practice

turning and circling.

by Audrey Pavia with Shannon Sand

0 comments:

Post a Comment