|

| Rollerblading at the Emmys |

Back in the 1920s, L.A.’s majestic Shrine Auditorium was the largest indoor theater in the world, and today its looming Moorish architecture makes it just as impressive a structure. On September 19, 2006, its gleaming yellow Persian domes cast long shadows on the red carpet for the fifty-eighth Creative Arts Emmy Awards celebration. The September afternoon was hot, and I was a little uncomfortable in my black shirt, tailored tux, and fancy dress shoes, but it didn’t matter. I couldn’t have been more excited. It was the second season of my show Dog Whisperer, and my team and I had been nominated for the first time, in the category of “outstanding reality show.”

“Cesar! Right here!” one of the paparazzi shouted. That’s what they do to get you to turn to look at them as they try to snap your picture.

“Daddy! Daddy! Look over here!” another one cried out. Standing next to me on the red carpet, wearing his best formal collar, my faithful pit bull Daddy instinctively looked up at the sound of his name. The photographers clicked away, and pretty soon all the attention was on him. Daddy being Daddy, he just took it all in with serene interest. Daddy was always up for new adventures, and nothing—not even shouting paparazzi and flashing lights—ever really fazed him.

Our turn on the red carpet came and went in an instant, and we joined the throngs of glittering guests pressing through the arched doorways of the auditorium. I might have looked just like all the other men in their standard penguin suits and bow ties, but waiting backstage for me were some special accessories for my outfit.

I had brought along my Rollerblades.

About an hour after the ceremony began, I peered out from the wings at the vast, packed theater—an old-fashioned opera house just like the one that Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom might have haunted, filled with plush red-velvet seats and ornate details and gold trim. Strangely, I wasn’t nervous at all. I was calm and focused when the words I was waiting for boomed out over the giant sound system:

“Ladies and gentlemen, the Dog Whisperer, Cesar Millan!”

The smooth voice of the female announcer was timed perfectly to coincide with the upbeat music cue of “Who Let the Dogs Out?” That’s when I Rollerbladed across the 194-foot stage at the Shrine Auditorium, with six happy pit bulls trotting beside me.

The audience gasped and applauded wildly. They burst into spontaneous laughter when Pepito, one of the pits, became hypnotized by our image in the giant video monitors that flanked the stage so that even those in the nosebleed seats could see the reactions on the winners’ faces when they came up to accept their statues. After my assistants had removed all the dogs except Daddy from the stage so I could do the actual presentation, I threw the envelope containing the names of the winners to Daddy and had him bring it to me at the podium. The audience roared again when Daddy, now off-leash, sauntered over to greet, sniff, and check out a very nervous Jimmy Romano, the winner in the “best stuntman” category. As we left the stage to make room for the next award presentation, I felt elated by how smoothly the whole production had gone, especially considering we’d only had one rehearsal earlier in the day.

When I was asked to present an award for the ceremony, I leapt at the chance to do something totally different. I wanted to show people that pit bulls are pack-oriented and that they can be wonderful and obedient dogs. The pits had come through with flying colors, and I was thrilled at how well we’d succeeded.

I wonder if the show director would have been so enthusiastic if I’d told him ahead of time that only one of those pit bulls was what most people would call “trained.”

I call them well behaved, and I call them balanced. But not one of those dogs had had any formal preparation to be on a stage, under bright lights, with loud music blaring, in front of 6,500 people.

So how did I create such a polite, open, obedient pack of pit bulls without what I would call “formal training”?

OBEDIENCE: WHAT’S YOUR DEFINITION?

In the opening of my show, I always say, “I rehabilitate dogs. I train people.”

There’s a reason for that claim. Usually, humans need much more help understanding their dogs than dogs need in understanding their humans. Dogs are hardwired to understand us. It’s in their genes to know how to read our facial expressions, body language, and changes of mood and energy. Dogs are the only animals besides primates that understand that when we raise an arm to point at a distant object, they are supposed to look in the direction we are pointing. Other animals can learn this, but it’s not natural for them. Their instinct is to just stare at our outstretched arm!

Humans, on the other hand, are constantly misreading dogs’ attempts at communication. Many people interpret any wagging tail as a signal of friendship, but an experienced observer of canines would notice that when a dog’s body language is tense, her teeth are slightly bared, and her tail is swishing slowly side to side, it means the exact opposite of “friendship.” You may think your dog is trying to punish you when she destroys your favorite shoes while you’re at work, but in fact she’s just frustrated and bored out of her mind. And if you reach out to “comfort” a nervous dog by petting her, you will only make her even more nervous. A dog in distress needs for you to stand strong and show leadership, not melt into sympathy because you’re feeling sorry for her. These are only a handful of the many ways in which humans misjudge what dogs are trying to say to them—and ironically, it’s these crossed wires of communication that are the reason I have a career today.

When my clients say they want an obedient dog, most of the time the situation has gone way beyond a dog that won’t sit on command. It’s about a dog that’s ruining someone’s life—or a dog whose own life is on the line if the owner can’t get its behavior under control. Even in less extreme cases, however, people’s definition of an obedient dog varies greatly, just as people are vastly different in what they want from their relationships with their dogs. Our relationships with our dogs are very personal, reflecting our individuality and the choices we’ve made for our own happiness. For example, I would never put up with some of the things many other dog owners think are just fine—such as jumping on anyone who walks in the door, barking excessively when someone comes up the driveway, or monopolizing the owner’s bed at night. In my experience, these behaviors can escalate into worse problems if left unchecked and can send your dog confusing messages about who sets the agenda in the household. In addition, you are not doing your dog any favors by letting him live without limits—dogs, like most creatures, thrive on structure.

But ultimately it’s your life, and your dog. Plenty of people—and plenty of dogs—live blissfully happy lives doing it their own way, and more power to them. I’ve handled cases in which the owner didn’t want to follow my prescription and decided, “I just love my dog so much, I’m willing to live with the problem.” Okay, that’s fair. Owners like these looked at their options and then chose to stay with the status quo. I don’t believe in judging other people or the way they raise their dogs—unless, of course, a person, society, or the dog itself is harmed in the process. I believe my job is to show people their options. It’s up to them to decide what to do with those options.

For most of my clients, a dog that rolls over, plays dead, or “speaks” on cue is not at all what they’re looking for in a canine companion. Most people don’t want a guard dog, a protection dog, or the winner of the next Frisbee Dog Olympics. In truth, many dog owners only dream of a warm, loving, comfortable companion with whom to share their lives. In their minds, it’s fine if the dog does his own thing at times, even having the run of the house, the yard, and the furniture, but they still want him to stay within a certain range of acceptable behaviors. Other dog owners are much more finicky. They absolutely do not want the dog on their $2,000 couch, ever, period, end of story. They don’t want their dog to dig up their precious rose bed. They want their dog to be able to get right into his crate on cue, ready to travel with them anywhere. The bottom line is that, with the exception of a dog that’s a danger or nuisance to others, what we want from a dog is a very personal thing.

We decided to do an informal survey in our Cesar’s Way e-newsletter, asking readers about the most important behaviors they want or expect from their pet canines. Four thousand readers responded by rating a list of ideal behaviors as “very important” to “not important.” Beginning on this page is a list of the questions we asked, with the results. As you read the list, take the survey yourself and think about these questions: What are your expectations for your life with your dog? How do you define an “obedient dog”?

As you can see, the same basic answers come up again and again. If you use Hollywood trainer Mark Harden’s definition, what people really want from their pet dog seems to be more manners than training.

When I worked at the dog training facility as a kennel boy, I remember that the big issue for everyone who came to the company was a dog that didn’t “come when called.” “My dog doesn’t come when called” was absolutely the biggest complaint we heard, and our informal survey shows that it is still right up there at the top of our readers’ wish list of behaviors they really want their dogs to exhibit. To get your dog to come when you call him, you’ve got to give him a reason to want to come to you. This begins with your bond, and it also involves understanding your dog’s motivation. We’ll go into the details of this in A WORLD OF WAYS TO BASIC OBEDIENCE - Step-by-Step Instructions.

My point is this: when it comes down to it, most people’s expectations for a well-behaved dog aren’t really that outrageous. The top items on the list are not much to ask for, and I’m happy to tell you that these things are not that hard to achieve, once you’ve established a proper leadership role and a bonded connection of trust with your dog. It’s my goal in this book to help you understand not only these basic foundations of creating a fulfilled and balanced dog, but also the wide range of options you have that will help you achieve all your other obedience goals as well. You don’t have to go to formal obedience classes, or learn to train with a clicker, or teach your dog to herd sheep or jump through hoops. But there is a world of opportunity out there that will help your dog reach his potential—and help shape your dream companion in the process.

The first key to gaining the obedient dog of your dreams is to define what obedience means to you. If you don’t know exactly what you want from your dog, how can you possibly expect him to give it to you? This is a personal decision that should be carefully considered and should involve everyone in the household. So take the time to think about it. Right now, sit down and make up a checklist of the qualities you would like to have in the dog that shares its life with you. Envision these aspects of an obedient dog and refer to this list and this image often as you read and think about the material in this book.

The first key to gaining the obedient dog of your dreams is to define what obedience means to you. If you don’t know exactly what you want from your dog, how can you possibly expect him to give it to you? This is a personal decision that should be carefully considered and should involve everyone in the household. So take the time to think about it. Right now, sit down and make up a checklist of the qualities you would like to have in the dog that shares its life with you. Envision these aspects of an obedient dog and refer to this list and this image often as you read and think about the material in this book. BALANCE FIRST

What is a balanced dog? I think of a balanced dog as one that is comfortable in his own skin. It is a dog that gets along with other dogs and people equally well, that understands the patterns and routines of his life but also welcomes new experiences, and that isn’t handicapped by behavioral issues like fear, anxiety, or obsession.

I’ve used the term balance around my colleague Martin Deeley many times, so I asked him what the word has come to mean to him. “What is balanced in my mind?” asked Martin. “A dog that is sound in body and mind—a healthy dog is the easy answer. Physical health is an easy one to identify. If a dog has any pain or is not feeling good, then obviously it does not train easily and may not even want to train or accommodate your requests. Health, though, can also affect the mental state, so we need to ensure we have a healthy pup as a foundation of a trainable dog.”

Ian Dunbar has a very personal story about a dog whose health affected his ability to be trained. “I have a rottie-and-redbone-coonhound mix, Claude. He’s getting pretty old now. And he blew out his cruciate. And so he had to have a TPLO [tibial plateau leveling osteotomy] operation. A tremendous operation. You go in and the dog walks out two days later. Within three days, his entire personality changed,” Ian recalls. “He became a totally happy, silly dog. We realized we’ve been living with a dog for five years who was in extreme pain. And that’s why he was slow to sit and slow to come and slow to lie down. After this operation, we had a totally different dog on our hands. So there may be very good reasons why the dog doesn’t want to come or sit.”

Then there’s the mental/psychological side of balance. “What am I looking for in a mentally stable dog, or a ‘balanced’ mind?” Martin Deeley ponders. “Like in ourselves, stability in dogs comes from rules, structure, and stability in life. We know what is going to happen, we know what to expect, and we are confident in how it all occurs. Even new situations, new people, new dogs, and other animals are approached with confidence and acceptance.”

If your dog is to achieve balance, he must be fulfilled as an animal first, then as a dog, then as whatever breed he happens to be, and then as your specific, individual dog with a particular name. You can read more in-depth explanations and instructions about how to create balance in your dog in some of my earlier books. Here I provide what I consider the basics for creating a balanced dog:

Cesar’s Rules FOR A BALANCED DOG

1. When you bring a dog into your life, don’t just think of what you want from him. Think first of what you need to give this dog to make him happy under your roof. Start by thinking of your dog as an animal, then as a dog, then as a breed, then as a name, and fulfill your dog’s needs in that order. In my experience, once you’ve fulfilled these needs of your dog, he will automatically want to fulfill your needs in return.

2. Of course you want a dog to love, but love is not the first or only thing dogs need to be happy. Just as with most humans, love alone is not enough. Follow my three-part formula—(1) exercise, (2) discipline (rules, boundaries, and limitations—this includes training!), and (3) affection—in that order.

3. Exercise: Exercise means at least one—and preferably two—long walks every day of forty-five minutes or longer (thirty minutes minimum!), depending on your dog’s breed, size, energy level, and age. Letting your dog run free in your backyard doesn’t cut it. By exercise I mean a structured walk with you by his side. This fulfills your dog’s need to work for food and water, in concert with his pack. It’s also the single most powerful tool you have at your disposal for creating a deep, meaningful bond with your dog—and on top of that, it’s free!

4. Discipline: Your dog’s mother began teaching him rules, boundaries, and limitations from the second he took his first breath. Rules aren’t something your dog resents—they are something he craves. Your job, as a dog owner, is to be clear and simple about these rules—and to always remain consistent about them! It’s important for any balanced dog to know the parameters of his world and where he stands in his pack.

5. Affection: Affection doesn’t necessarily mean petting, and it doesn’t necessarily mean treats. First and foremost, it means the bond of trust and respect between human and dog. A person with no arms can have a bond of affection with her dog, even if she’s unable to pet him. The beautiful thing about dogs is that when you show them honor and respect, they return the same to you a thousandfold. Dogs are perhaps the most generous and fair beings on the planet. Beyond that, being affectionate with your dog in any form—sharing games, toys, adventures, treats, and, of course, massage and petting—is incredibly good and even therapeutic for you as well as your dog.

BALANCE ACCOMPLISHES MIRACLES

So, back to the original question: How did I get six pit bulls to perform onstage at the Emmys in front of thousands of people without formal training?

I believe that balance accomplishes miracles. I had made sure that the six pits I brought with me to the Shrine Auditorium that day—Daddy, Pepito, Spot, Pattern, Sam, and Dotty—were balanced, but in fact not all of them had begun life as a well-behaved pup. Sam was afraid of people and children when he first came to me, and Pattern had been dog-aggressive when I met him. Both dogs belonged to my friend Barry Josephson, a Hollywood film and television producer. Spot came to me from Much Love Animal Rescue because he was dog-aggressive. These dogs had lived with me and my pack for weeks and months, and because of the work I did with them, by the time we all went to the Emmys together I totally trusted all three of them to behave well in any completely new and challenging situation. I believe almost all dogs have the ability to change their negative behavior—under the right circumstances and in the hands of the right humans. But most important on Emmy night, all of the pits totally trusted me in return.

The changes I produced in these three troubled pits didn’t come instantly or without consistent hard work over a period of time. Despite the quick turnarounds you see on Dog Whisperer, no change in behavior becomes permanent without regular practice and repetition. Even the happy families with dogs that are cured at the end of each episode have to follow through with their own behavioral changes, every single day, or their “transformed” dog won’t remain transformed. At the Dog Psychology Center, my staff and I had worked hard to fulfill the lives and basic needs of all six Emmy pits on a daily basis, providing them with vigorous exercise; a set routine; clear boundaries and limitations (discipline); plenty of challenges, such as obstacle courses, ball-playing time, swimming, and other games; outings to new places like the beach and the mountains … and of course, healthy food and affection. In my experience, even dogs that have come from horrific pasts filled with abuse and neglect can and do come back to balance eagerly and willingly, whereas a human with the same kind of “baggage” might be forever haunted by bad memories. Dogs don’t hang on to resentments, so they can change and adapt much more readily than humans. But it’s up to the humans to do the work to make those changes stick. That’s why, to me, it’s the owners who are the hard part of the dog rehabilitation equation, not the dogs.

The six pits that came to the stage with me that day lived with me daily and knew what I expected of them as well as exactly what they could expect from me. Just as dogs living with each other in a pack have a very basic set of rules of behavior, I too want very basic things from the pack that lives with me.

My rules and conversations with the dogs in my pack are simple and clear: my aim is to define for them the rules of life that are essential for their survival in a particular environment. And the basis of that communication is always the same—trust and respect, from human to dog, and from dog to human. It has to work both ways.

Christine Lochmann and Tina Madden, two of my assistants from the Dog Psychology Center, came along with me for the afternoon rehearsal. When I went back home to change into my tux, they were responsible for preparing the dogs for the evening’s performance.

“All six pit bulls were what Cesar calls ‘balanced,’ or well behaved, but only Daddy had any formal training. None of them were really trained in the ‘sit,’ ‘stay,’ ‘come,’ ‘heel’ kind of way,” Tina recalls. “They weren’t performing dogs. This would be their first time on a stage, with bright lights, in front of an audience of hundreds of people. It was [our] job to keep them relaxed and happy backstage so they’d be in the right state of mind to go onstage.”

CESAR’S SIMPLE RULES OF GOOD PACK BEHAVIOR

1. I’m the pack leader. Trust, respect, and follow me.

2. You don’t have to figure out what to do when I’m around. Just wait for me to tell you what to do (including the many times I’ll release you to “just relax and have fun!”).

3. We always interact politely with other dogs and humans. We always avoid situations where there might be conflicts.

4. No fighting with each other.

5. I’m the one who starts and stops all play activity that we do together.

|

Backstage at the Emmys |

How do you prepare six pit bulls for their first command performance? First of all, we made sure that they had all their physical needs met—elimination, water, and exercise, though I asked Tina and Christine not to feed the dogs that day. Fasting until after the event would make them more motivated, and if I had to use food to inspire their performance, a hearty appetite would make them more likely to pay attention. Their dinner afterward would then become a celebration and a really big reward. In the morning we took a long run with them—longer than usual. And of course, we bathed and groomed them so they would be looking their very best for the cameras.

“At nighttime, after the rehearsal, Christine and I went downstairs and walked the dogs again,” says Tina. “We were in makeup and dresses and were walking around in heels outside the Shrine Auditorium, with this pack of pit bulls in tow. After a good long walk, we went backstage and waited. Cesar would be in the audience, and we wouldn’t be able to see him until, like, fifteen minutes before the actual presenting.”

Whenever you bring your dog into a new and possibly intimidating situation, it’s important that the dog understand as much as possible where he is and what is happening to him. We made sure not to just take the dogs from the van, stick them in a room, and then bring them onstage. We walked them from backstage to the room a couple times to get them familiar with the route. We also played a little bit of ball to keep their minds challenged and to get their energy up into what I call “a happy hype.”

A balanced dog, in my book, is one that doesn’t get carried away in a chaotic situation—as long as her pack leader or owner stays calm. Tina and Christine were great pack leaders backstage. They kept the greenroom tranquil, prevented overexcited humans from overstimulating the dogs, and let the dogs know at all times that they were safe and in good hands.

“The dogs weren’t overexcited at all—they were relaxed and happy, thrilled to be in a new environment, and interested in everything that was going on around them,” says Tina. “I must have had at least ten people come up and say, ‘These dogs are so well behaved.’ Somebody even wanted to adopt Spot after meeting him.”

Finally, it came time for me to present the award for best stunt. Tina and Christine brought the dogs upstairs, and I met them backstage with my Rollerblades on. It was a very narrow area, and we were climbing over cables and squeezing past stagehands who were running by, doing their thing all around us.

When you bring a dog into an unfamiliar situation, introducing something he is already familiar with can ease the transition. Definitely, my trusty Rollerblades were something the six pit bulls were familiar with. The minute they saw them, they understood, “Okay, this is something fun. We’re going into migration mode!” Since I had Rollerbladed with them through the busy, loud, distraction-filled streets of South Central so many times before, they were well prepared to Rollerblade calmly past most any other chaotic and noisy situation we might encounter. They also knew that when I stop, they stop—whether to cross the street or to let other people or dogs pass by. Seeing the Rollerblades, the pack collectively gave me a look like, “Okay, we get what you want us to do next!” And Rollerblading is something they absolutely love, so their energy was up, excited, and positive.

The energy around us before we went onstage, however, was tense and frenetic, and we couldn’t totally prepare them for that. That atmosphere could have created an anxious response in them if that was all they were paying attention to. But because of my relationship with the pack, they took all their emotional cues from me. Since I felt safe and calm and made it clear that all the commotion hadn’t changed my state of being, they were able to mirror my energy as they went through the same experience. This is the payoff of a strong leadership bond with your dogs. When the dog’s reaction is, “Oh, this is new for me,” he looks at you. If he sees that you’re still calm and communicating clearly what it is you want from him, he thinks, “Okay, fine, I guess we’re going to do the same thing we’ve been doing when a bus passes by, when somebody blows a car horn, or when somebody opens an umbrella.”

The Emmys show presented new, unexpected, and potentially unsettling experiences, but the dogs had shared at least a thousand similar experiences with me before and everything had been okay—and even fun. So the Emmys became their new experience number one thousand and one. It was just another great adventure for all of us to share.

It was a long day for everyone. While I got to go home in the limo, Tina and Christine drove the pack of tired but contented pit bulls back to the Dog Psychology Center in their large rented van. “I remember as we were driving through the really rough neighborhoods in South Central Los Angeles,” Christine says, “Tina just looks at me and starts smiling. She goes, ‘Do you think we’re safe here with six pit bulls in the back of the car?’ We had a blast. It was a magical night.”

I recounted this wonderful experience of ours for a reason: I want to make clear to you the amazing things you can accomplish with your dog through balance and a strong leadership relationship alone.

Cesar’s Rules FOR BRINGING A DOG INTO A STRANGE NEW SITUATION

1. Don’t throw any dog into a new situation without some prior preparation! Find creative ways to “rehearse” well in advance of the main event. Make sure your own demeanor is calm and steady. The more times you’ve shown leadership in different environments, the more your dog will trust you even when she’s unsure.

2. If it’s a situation where you can prepare the dog in the actual environment itself, even better! Let the dog associate the new place with relaxation, fun, affection, and treats.

3. Bring along something familiar to your dog, something that represents calmness, comfort, or joy. For example, for the pit bulls the Rollerblades were a symbol of their very favorite activity.

4. Fulfill your dog’s basic needs—on a regular basis of course, but especially on the special day. Extra exercise is always helpful—a tired dog with no pent-up energy is more likely to be relaxed rather than stressed in a new situation.

5. Finally, check your own energy. Are you yourself unsure in the new situation? Are you nervous or distracted? If you are, how can you expect your dog to stay calm? Deal with your own fear, or anxiety, or frustration, before you bring your dog into the picture.

TRAINED DOESN’T NECESSARILY MEAN BALANCED

At the Emmys, I was able to get amazing performances out of the pit bulls because they were balanced and we had a solid bond and clear, consistent communication between us. The dogs knew exactly what I wanted from them, and I knew what they wanted and needed from me. Isn’t it amazing what is possible to achieve with six fulfilled dogs using just balance alone? Another person might bring six “trained” dogs up on the same stage. Those dogs might be able to sit, stay, roll over, and jump through hoops. But what if there is an accident backstage, or someone on the crew panics? If the dogs are trained and not balanced, you can still run into trouble.

The truth is that, as human beings living in an often stressful, competitive world, we all have known members of our own species who are trained—or highly educated or credentialed—but definitely not balanced. I believe the world is in a fight-or-flight avoidance state because we have very intelligent people ruling the world, but not necessarily the people with the best common sense or the people who genuinely have the good of the rest of their human “pack” at heart. We need more of those people in positions of power in order to return our own world to balance.

The same thing applies to dogs. On Dog Whisperer and in some private cases I’ve taken on, I’ve worked with dogs that are among the most highly trained animals in America, yet because their needs as animal-dog were not being fulfilled, they were unbalanced and therefore unreliable in one way or another. Some of them were frustrated and aggressive, some were obsessed in some way, and others had developed fears and phobias.

|

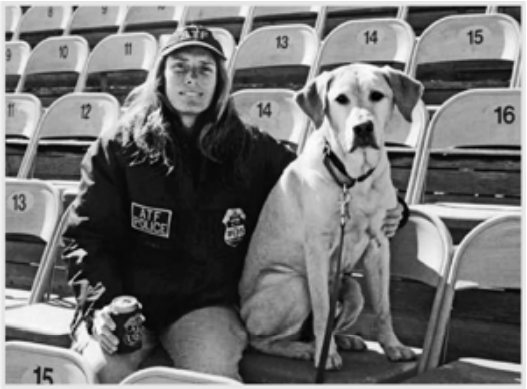

| Cesar works with trained explosive-detection dogs in Miami. |

VERY SPECIAL AGENT GAVIN

L. A. Bykowsky is a twenty-five-year veteran of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). In 2002 a new responsibility was added to her official duties—canine handler. A special dog was chosen for her—a gentle, calm, well-behaved yellow Labrador retriever named Gavin.

Together, L. A. and Gavin went through the ATF’s Explosive Detection Canine Training Program. Gavin graduated with the ability to detect the scents of up to nineteen thousand different explosives. His protocol after being asked to search was to sit down whenever he detected a target scent. Gavin’s new skill put him on the front lines of the war against terror.

Immediately after graduating, L. A. and Gavin embarked on their new career adventure together. “I’ve actually spent more time with Gavin in the past five years than I have with my husband,” L. A. told me. They worked several Super Bowls and NASCAR events before being sent on a mission in Iraq.

|

| L. A. Bykowsky and Gavin the ATF dog |

“In Iraq he never once shut down,” L. A. said. “When loud noises went off, he quivered and shook, but then, so did I.” Clearly, Gavin was stressed out by the experience, but he stuck to his training protocols and continued to work. However, immediately after he returned to the home he shared with L. A. and her husband, Cliff Abram, in coastal Pompano Beach, Florida, he faced the additional trauma of two back-to-back hurricanes. The trauma of the wind, rain, thunder, and lightning, followed by a Fourth of July celebration with exploding fireworks, finally pushed his frayed nerves over the edge. “He ran from room to room to room,” Cliff remembers, “and couldn’t stop shaking. He wouldn’t even eat. After that, you couldn’t pick him up and bring him into the house.”

Once Gavin snapped, any noise at all—answering machines, phones, alarms, fire alarms—would turn him into a quivering lump of Jell-O. Suffering from what L. A. concedes was a canine form of post-traumatic stress disorder, Gavin was forced to retire from his five-year career of decorated service to his country.

“What I really want for Gavin is to be able to enjoy his retirement and to not be afraid all the time,” L. A. told me when I went to visit her and Cliff in Florida.

Gavin was a highly trained dog, but his training hadn’t prevented him from developing a very serious behavior issue, an issue that threatened not just his own well-being but that of his family as well. My sense from the moment I first met him was that this was a dog that hadn’t been allowed to be himself—meaning, just an animal-dog first—for a very long time.

“The work he has been doing is not instinctual. It’s not instinctual to sniff out explosives. It’s instinctual to sniff out a duck. The explosives stuff is created by humans, for humans,” I explained to the couple. “He has been Gavin, Labrador, ATF. Not animal, dog, breed, name.”

Cliff nodded thoughtfully as I spoke. “When they finished the ATF course, they told us, ‘He’s not a pet anymore, he’s a tool.’ In all that time, you forget he’s a dog.”

It was my goal to help Gavin recover the essential “dog” in himself. I asked L. A. and Cliff if I could bring Gavin back to South Los Angeles with me.

At the Dog Psychology Center, Gavin was welcomed by the pack in our traditional quiet way—no touch, no talk, no eye contact. The pack approached him and sniffed him and instantly accepted him as one of them. When you watch dogs greet other dogs, you will see that much of their communicating is done in silence. The nose comes first, then the eyes, then the ears. They talk to one another through scent, then eye contact, then body language, and finally touch. Human training, on the other hand, is almost always ears first. That was the style of training used by the ATF to turn Gavin into a heroic working dog. On his first few days living with the pack, I’d rely mostly on the other dogs to help him relax into our routine. As I’ve seen hundreds of times, a pack of dogs can do more rehab in a few hours than I can do alone in a few days.

By the beginning of his second week with us, Gavin had relaxed visibly, and he and I had started to get to know and trust one another. We did fun, silly things like go on hikes, play catch, go for runs along the beach—things that would help Gavin remember the pure joy of just being a dog! Truth be told, I was already falling in love with the guy.

The Dog Whisperer crew went on the road to San Diego, and I decided to take Gavin along with us so that I could observe how he reacted in new situations. He did amazingly well. I even let him play the role of a calm-submissive dog in order to help some out-of-control dogs for the show. He and Daddy had already hit it off when we met Gavin in Florida, and they made a great team of Dog Whisperer canine assistants. I could see what a sweet, gentle soul Gavin possessed. He was calm and confident all day, and I didn’t see any signs of the fearfulness that had brought him to rehab in the first place. I was beginning to think this might be a slam-dunk case.

I was wrong. When we returned to our hotel that evening, I brought Gavin with me into the elevator, and when the floor alerts started to beep, he descended into a fearful state again, lowering his head and putting his tail between his legs. He didn’t run or try to hide, but he just sat down, in the same position he was trained to assume whenever he found explosives. Somehow his trained response had become his default response to stress. I knew I was going to have to figure out a new strategy to help him break through this fear.

Over the next thirty days or so, I continued to use the pack and playtime to build a trusting bond with Gavin, while gradually introducing new experiences and sounds to him. L. A. had told me that carrots were Gavin’s favorite treat, so I’d toss a carrot to him at the same time as I’d expose him to a loud but unthreatening noise, like heavy footsteps or the crumpling of a paper bag. I increased the intensity of the sound very slowly as Gavin showed me that he wasn’t going to shut down near it. In the early phases of the therapy, sometimes he would sit down, freeze, or avoid the noise. My response was to ignore him for a moment. Gradually, he stopped fleeing and instead came and stood by me. That was a big change, because he had been running away from L. A. and Cliff when he was nervous. “If you come stand by me, buddy, I can influence you with my calm energy,” I whispered to him. It was gratifying to me that he was looking to me as a cue for how to behave.

The next level of challenge was to encourage Gavin to walk toward a loud sound, then to reward him when he reached it. I took advantage of his ATF training and hid treats in and around a boom box, commanding him to “search” for his rewards. The combination of his ingrained training and his love of treats worked to overcome his aversion to the speakers and the sounds coming out of them. Soon I was making feeding time itself a loud experience for him. I’d shake the food up and down in a metal bowl and call him over to the sound, then feed him. Associating mealtime with a loud noise also helped to quell his anxiety.

To make sure Gavin wasn’t overexposed too soon, I didn’t let any of these exercises go on for longer than five minutes. We’d do five minutes of stress exposure, then run and play in the pool for fun. Gavin caught on quickly that he’d get his favorite reward—playtime or pool time—after every completed exercise, so even the challenges became something he’d look forward to.

As the weeks passed, I continued to bring Gavin onto the set for a variety of different Dog Whisperer stories. I found him so appealing that I wanted to be around him all the time. I even brought him to my home, where he and I practiced tricks in the garage while my son Calvin, then eight, practiced on his earsplitting new drum set. Gavin never even flinched at Calvin’s drumming—which was more than could be said for our neighbors!

Another feature of Gavin’s rehabilitation was regular acupuncture treatment. Acupuncture stimulates endorphins—the brain’s natural painkillers—and other feel-good neurotransmitters. I’ve found acupuncture to be incredibly beneficial in my own life as a way to deal with stress and anxiety, and animals, it seems to me, respond to this ancient Chinese art even more readily than humans do. It’s been especially helpful in cases of extreme fear, depression, or anxiety.

Play continued to be a major part of Gavin’s return to serenity. On day forty-eight of his rehab, a couple of old friends from Gavin’s ATF training school days, Todd the handler and ATF agent Corey, Todd’s black Lab, came by the Dog Psychology Center to visit. Corey and Gavin remembered each other right away and went into a boisterous Labrador celebration dance. Their reunion turned into an impromptu giant pool party for all the dogs at the center; taking center stage, Corey and Gavin would fly off the platform into the water and send tidal waves of splashes onto every human and animal in the vicinity. I had seen the playful side of Gavin many times before, but never anything as carefree and unbridled as he was with Corey that day. Once again, another dog had succeeded in moving Gavin’s rehab forward, right when I was worried that it was beginning to stall. Corey and Todd’s visit became another milestone in Gavin’s forward progress.

I believe in relying on Mother Nature first and foremost when working with dogs—but there’s no reason not to take advantage of modern technology when it can help! On day fifty, I finally introduced Gavin to the high-tech virtual-reality trailer that I had invented to take him to the next stage of his rehabilitation. I retrofitted an old Airstream with a video projector, surround sound, and a lighting grid, and I even set up jungle plants and a sprinkler system to simulate a rainstorm. With the help of three members of my Dog Whisperer “pack”—Murray Sumner, Todd Henderson, and Kevin Lublin—I designed three virtual-reality scenarios based specifically on the things that Gavin feared the most: a thunderstorm, a fireworks display, and a combat scenario.

|

| Gavin’s pool party |

Dogs can focus well on only one thing at a time, which is why I often use a treadmill to distract an anxious dog’s mind and focus his physical energy. Most dogs come to love walking on the treadmill—some even become addicted to it! I started Gavin at a slow speed, two miles per hour, and tried him out with just a little rain and thunder. Focusing on the treadmill, he was doing just fine, so I added more rain and some light flashes to represent lightning. While we raised the volume and intensity of the storm, I commanded Gavin to search for treats in the plants that lined the trailer, and when he found them, I asked him to “speak.” He remained happy, calm, and motivated throughout. Despite our success, however, I made sure the first session lasted only a few minutes. As a reward, we raced outside for a splash in the pool.

I was very proud of the whole concept of the virtual-reality trailer, and I hope to use it as a blueprint for other extremely fearful dogs. It’s important to note, however, that I didn’t rush Gavin right into facing the worst of his fears. We were almost two months into daily, intensive rehabilitation before I introduced him to this strategy. Before that, I focused on restoring his peace of mind by just letting him be a dog.

Over the next few days I exposed Gavin to both the fireworks and the combat scenarios in the trailer, rewarding him when he succeeded and finishing every short session with a vigorous play period. For his final challenge in the trailer, I had Tina Madden fire off a starter pistol. The first two times, Gavin tried to bolt off the treadmill. I slowed the treadmill speed while calmly redirecting him to keep going as if nothing had happened. The third time, he kept his eyes on me for reassurance but kept right on walking. That session got him the most joyful praise from me and the biggest reward and play break of them all. We were both so happy at his success.

Once I was certain that Gavin had mastered the virtual-reality trailer scenarios, I took him to the setting of his real final exam—an actual firing range. To give him an advantage, I brought along Chipper, a ridgeback/boxer mix, who was unfazed by any noise or commotion. I knew Chipper’s calmness would rub off on Gavin. While the proprietor of the firing range shot his rifle, Gavin, Chipper, and I ran back and forth behind him. After he passed the first few minutes with flying colors, I ran Gavin over to a kiddie pool I had brought with me, so he could get a little of his favorite reward, the favorite thing of all Labradors—water. After a few more laps around the firing range, I was convinced that my good little soldier Gavin was ready to graduate from my boot camp.

Seventy days after Gavin arrived at the center, L. A. and Cliff arrived to bring him home. It took him a moment to figure out who they were, but once his scent memory kicked in, he was all over them, jumping with joy. I proudly showed Gavin’s owners the virtual-reality trailer I’d made just for them. But what really knocked them out was seeing Gavin splashing ecstatically in the pool with his new friends from the pack. “We’d never seen him like this,” L. A. said. I like to say that I don’t favor one dog over another at the Dog Psychology Center, but Gavin had such an amazingly special way about him, it brought me to tears to say good-bye to him. I was content, however, because the transformation from Gavin the ATF agent to Gavin the happy-go-lucky Labrador was complete.

For Gavin, his training had actually worked against him when he came under the stress of battle, hurricanes, and fireworks, because he didn’t know how to just be a dog. Even a dog as highly skilled as Gavin must have his animal-dog-breed–related needs fulfilled before he can be expected to perform his human-imposed duties.

VIPER THE CELL-PHONE DOG

Viper the cell-phone dog is another example of a well-trained dog that was severely unbalanced. Viper’s behavior issues—extreme fear and lack of confidence—were preventing him not only from performing the functions he’d been trained for but also from having the close, loving bond that his owners very much wanted with him.

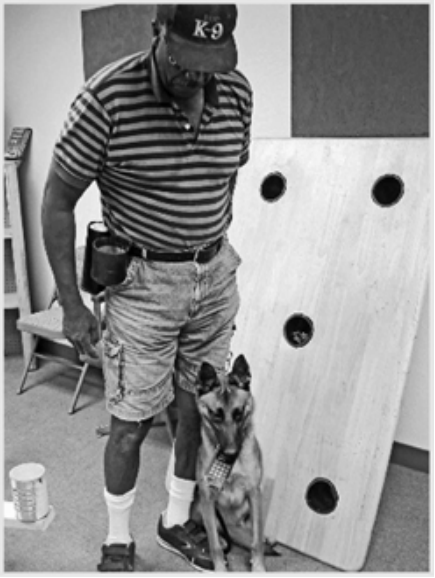

Most people don’t know that cell phones are considered the number one most dangerous contraband to be found inside of maximum-security prisons. With a cell phone, an inmate can arrange a crime, put out hits on witnesses, arrange gang violence, and orchestrate drug trafficking both inside and outside prison walls. In 1995, decorated former Fullerton, California, police officer Harlen Lambert founded All-States K-9 Detection Agency, which in 2007 became the first facility in the nation dedicated to training dogs to detect the specific odor of cell phones. Harlen came out of retirement to oversee this incredibly specialized scent training. “That’s my giveback to society,” he says. Harlen’s dogs are so highly trained that they can seek out and find the individual components of a cell phone, such as the battery and SIM-card, if an inmate has disassembled and hidden the parts of the phone in various locations. Inmates also try to foil the dogs by putting their cell phones inside food containers, the idea being to disguise the scent of the components with other strong smells, but the ASK-9 canines are not easily fooled. These tenacious dogs are trained to find cell phones inside mattresses, freezers, books, peanut butter, and garlic, and even underwater in a toilet tank.

|

| Viper and Harlen Lambert |

Harlen has trained hundreds of dogs over the course of more than thirty years, but one dog has earned a very special place in his heart: Viper, a three-year-old Belgian malinois. “He’s the smartest dog I have,” says Harlen. “He can find a cell phone in a field of approximately one hundred yards. He will not stop until he finds the phone.” The only rewards Viper seeks are a play toy and the joy and approval of his handler, Harlen.

The problem is that, for all his smarts, Viper is afraid of people and afraid of loud and sudden noises. Prisons are noisy, unpredictable environments. Viper can’t use his stellar skills unless he’s in totally controlled conditions. To demonstrate Viper’s problem to my Dog Whisperer crew, Harlen had us wait outside a one-way glass window while Viper quickly and accurately found the phones hidden in a mock-up room. Alone with Harlen, his tail was up, and he was energetic, happy, and playful. Then one of the cameramen and segment producer Todd Henderson entered the room, and Viper became a completely different dog. His body posture shrank, his tail went behind his legs, and he completely shut down.

“We learned after we got him that he had spent the first eight months of his life in a crate,” Harlen told me, shaking his head in disbelief that such a beautiful animal would be confined in such conditions. “So his skittishness isn’t just a habit; it goes really deep.”

Harlen is a tough, burly ex-cop, but the more we talked about Viper, the more emotion I could see welling up in his eyes. “I hate to see him unhappy. If I ever have to pull on him or force him in any way, it upsets me more than I think it does him. He’s so gentle. All he wants to do is please. This dog will never be for sale. Viper will never leave me.”

I asked Harlen if Viper had ever had a chance just to be a dog. Harlen said he’d take Viper to a dog park, but he would always be by himself. “He needs to have a pack of dogs,” I thought to myself. “He is so stressed out, completely rock-bottom. Viper really needs a vacation!”

After Harlen and his wife, Sharron, gave me permission to bring Viper back to the Santa Clarita Dog Psychology Center in California, I wanted to make sure I spent time with him before leading him out of the facility. But even after I’d sat quietly with him for several minutes while he calmed down and got used to my presence, he still froze up when I tried to gently lead him with a leash out from under the mock-up prison bunk on which I was sitting. So I did what I have done for many years when I get stuck on a case. I called in a Dog Whisperer with more wisdom than me.

Daddy.

Even at fifteen years of age, struggling with stiff bones and arthritis, Daddy performed like the total pro that he always was. As soon as Daddy arrived, Viper stuck his head out from under the bunk to sniff him, and a silent communication went on between them. It took only four and a half minutes for Daddy to lead a very willing Viper out of the room. Daddy became the link of trust between Viper and me. Once again, Daddy had my back.

“I don’t believe what I just saw,” said Sharron when she witnessed how instantly and enthusiastically Viper responded to Daddy. “It almost made me cry,” said Harlen.

Viper was rock-bottom when I took him. Any dog that spends the first eight months of his life—the most important months developmentally—in a crate is going to have a lot to overcome in life. Viper had no self-esteem or confidence whatsoever. I needed to remove him from his environment and start fresh in a new place.

The first thing I did was bring him into the Dog Whisperer mobile home, where he was greeted by the pack. The presence of a group of laid-back, friendly, balanced dogs had an immediately relaxing effect on him. By the time we arrived back at the ranch, it was still daylight. I wanted him to just be able to express the dog inside him, so I let him run with the rest of the pack in the wide field I call the sheepherding area. By the time it was getting dark, his nose kicked in, and he finally came right to me, without a leash or any other type of coercion.

During the first week with me Viper became a member of the pack. Through the dogs in the pack—Viper’s new family—I gradually earned his trust. He loved going on long runs through the hills and on hikes in the mountains.

While living with Harlen, Viper had become fearful of every tool there was—from a choke chain to an e-collar to a simple leash. Any of those items—and even just the presence of a stranger—would cause Viper to shut down immediately. Because a human was connected to all of these tools that Harlen had tried to use, and since we live in a world in which dogs must be controlled on-leash, I needed to transform these tools into a healthy experience for Viper. I had to wipe the slate clean and reintroduce him to them as if it were the first time he’d seen them.

I started with the basics: I needed him to be familiar with a simple leash so that I could take him off the property and give him the exposure to new scenarios that would be a major part of his rehab. Viper is a natural ball player, so once he became engaged in playing with the ball, it was easy for me to put the leash on his neck. Soon the leash had a positive association—ball time! In dog training, most people put the leash all the way at the base of the neck. If you’ve watched my show, you know that I like to place the leash all the way on the top, so it gives the dog less of an opportunity to control the situation by pulling. From that point on, Viper realized that if the leash was all the way on the top, he had to move forward. After that, he just relaxed because that’s what he’d wanted to do from the beginning. It was just that nobody had known how to help him get over this fearful obstacle.

The following week, right in the middle of Viper’s rehab, I had to fly to New York for some business meetings, book signings, and television interviews. I needed Junior and Angel for the television appearances, but I decided to take Viper with us as well. The trust he and I were building together was still fresh, and I didn’t want a setback. And for a dog that was afraid of people and commotion, New York City would be an amazing challenge. But I’d already seen such progress in Viper that I wanted to raise the stakes in his rehabilitation. Angel and Junior already knew how to be comfortable in places like New York, so Viper would be able to follow their calm example. When I was busy with appearances, producer Todd Henderson kept the dogs busy. As close as I was getting to him, I also didn’t want Viper to get so attached to me that he would see me as the only human who could help him.

|

| Dog Whisperer producer Todd Henderson with Viper in New York City |

Todd is a long-distance runner, so every day in New York City he took Viper and Junior running with him in Central Park. “One day I decided to march straight on down to Times Square, to actually walk the thirty-some blocks into the heart of midtown Manhattan, with all of the lights, all of the people. To have Viper continue to walk with me right into the heart of the beast and not be afraid—that was really exciting. That was the highlight of my trip.”

I was still in New York on day sixteen of Viper’s rehab, and I decided to use a tool I rarely use—a flexi-leash—to give him a little less structure. Because Viper had a tendency to get a bit clingy with the few humans he trusted, I wanted him to be able to resolve some of his anxiety issues on his own, rather than constantly relying on me to provide the solutions for him. He did amazingly well—through Central Park, all the way to the Museum of Natural History. There were joggers and bikers passing by us, Rollerbladers, strollers, and Viper’s biggest fear, skateboarders, but he just kept moving forward. With every new adventure, I could see his confidence growing.

Once we were back in L.A., I continued to take Viper to new places—Venice Beach, Hollywood Boulevard, a photo session with lots of lights and commotion. I even brought him along on a few Dog Whisperer episodes.

Creating Good Vibrations

As Viper grew stronger and more confident, I decided to try to replay a scenario that had been very traumatic for Viper the first time I’d witnessed it.

When Harlen Lambert brought Viper out of his kennel that first time I met him, all the yanking and resistance was a very traumatic experience for both of them. Harlen was pulling and tugging, and Viper was pulling and tugging in the other direction, and eventually Viper just shut down. Harlen became distressed at having upset Viper, so the energy between them was tense and negative. The leash and the collar worked against the relationship and had damaged the trust between them.

Although Viper had already become accustomed to a leash, I didn’t want to undo the work I had done with him by allowing him to associate the leash with the only reason he comes out of his kennel. I decided to use a vibrational e-collar to give guidance to Viper from a distance and enable him to believe he was making his own decisions and was not connected to a human with a leash.

It’s important to note that an e-collar of any type is a short-term, not long-term, solution to a behavior problem. If you have to use it long-term, you’re doing it wrong. Never use an e-collar in standard obedience training or to add a new behavior. And whenever you introduce any new tool, make sure your dog is comfortable just being around the tool before you use it to try to change his behavior. Viper had already been upset by the e-collar that Harlen used, so I took my time to create a positive association for him with just wearing the collar on a casual basis. Once he was comfortable having it put around his neck, I had him wear it as a matter of course for weeks before I ever pressed the button. He did all the activities that he was already familiar with, both with and without the e-collar, so he would get used to having the weight of it sometimes and not having the weight other times.

About twenty-eight days into his rehab, I determined that Viper was comfortable wearing the new tool. We had already done the hard work together to build a solid platform of trust. Only then did I set out to redo the scenario in which I invited him to come out of his kennel and join the Dog Whisperer crew—a pack of humans that now represented family and good times to him. In the past, when Viper was nervous, shy, or unsure in a situation, he wouldn’t just go into flight state—he would turn his back to the wall or find a place to hide and completely shut down. Viper’s reaction was in fact worse than a full-out flight reaction, because at least when an animal is fleeing it’s taking a positive action, in forward motion. Viper’s freezing up was the opposite of the behavior of a balanced dog, which, even if cautious, is always curious.

The reason I chose this tool for this particular situation was to separate Viper’s experience of me—or any human—from his experience of a correction (such as the pulling of a leash) that told him not to run away from humans. It also allowed him to have the feeling of choice—that is, the freedom to come out of the kennel and the freedom to be with people. It’s important to take note of when I did and didn’t use the vibration. If I’d used the vibration when he started to run away, then he would have related the vibration to the person or object he was running away from. This was not what I wanted. Instead, I used the vibration when he stopped moving away and went into freeze mode, or when he got to the wall or fence or whatever place he was trying to hide in. That encouraged him to go away from the hiding situation and back toward the human or thing where he didn’t have the vibration. The vibration became a simple communication—a yes or no, a way of saying “Getting colder” or “Getting warmer.”

Because of Viper’s severe lack of trust in people in the past, it was important to create a “circle of trust” for him among the crew members, who stood quietly and ignored Viper and let him figure out the vibration on his own. As Viper moved away from the vibration, gradually he realized that people were not trying to grab him or make him do anything. He was able to choose on his own to move away from the wall or hiding place where he felt the sensation and toward the humans who were not putting pressure on him to perform. We let Viper take his time and come to his own conclusions, which became, “It’s a warm, comfortable place within the circle of humans, and not as comfortable a place when I run and hide away on my own.”

When, nine minutes later, Viper finally came to me and joined us inside the Dog Whisperer circle, I rewarded him with praise and petting. Junior came to him and licked his face, giving his own form of reward and also saying, “You can relax, it’s okay out here.” This is one more good example of why I always use dogs to help other dogs. They can get the message of trust across much faster than we humans can. As you can see, the e-collar wasn’t even the most important tool I used in this exercise with Viper. The most effective tools were the warm, patient, calm-assertive energies of the crew members and the support of Viper’s canine friend Junior.

On day thirty-seven, I decided to give Viper his toughest challenge yet. I brought him to a busy skateboard park in Santa Clarita, one that my boys like to frequent. My goal was to desensitize him to the skateboard noises—not by telling him how to do it, but by letting him figure out that nothing bad would happen to him when he was around strange sounds. Once again, I used the flexi-leash to give him some room to solve his own problems and to keep him from using me as a crutch or a way to hide from the things he feared.

First I walked him all around the park. Whenever you are working with a dog, always introduce him to his environment before you introduce him to the challenge.

|

| Viper, Cesar, and Calvin at the skate park |

I wanted to free Viper from his fears by immersing him in the sounds and movements he used to be so afraid of. But once again, it’s important to note that I didn’t just start working with him and throw him into the skateboard park from day one. This was more than a month later, after we’d been through the chaos of New York, the hustle and bustle of Hollywood, and regular nightly practice at my home with a single skateboard, thanks to the participation of my son Calvin. This was more like a final exam for Viper.

As we got closer to the park, the noises got louder. Viper didn’t shut down the way he used to, but I could see he was alert and nervous. To help him out, I brought him his human pack—my sons Calvin and Andre. He definitely relaxed in their presence. Whenever you are exposing a dog to something new, it’s helpful to bring in people, dogs, or things that signify relaxation to him. Next, all four of us sat beside the skateboard rink and just watched the action for about five minutes.

I was proud of Viper—he was alert but not too anxious. After a few minutes, I brought him back out to the quiet green surrounding the park so he could have a break; then we returned to the concrete skateboarding rink once again. By the third time around the park, Viper was walking in front of me, relaxed, confident, tail high, despite the fact that the skateboard action was still going on all around us. It was a very successful day—a day when confidence and trust overpowered irrational fear.

On day fifty-five, we brought Viper home to Harlen and Sharron Lambert. Viper had come up from rock-bottom. He was still a slightly hesitant, cautious dog, but he had a new confidence and a much more measured way of responding to things that made him anxious. I brought the pack along with him in the van, for moral support.

When I arrived at Harlen’s place and opened the tailgate, Viper immediately leapt out and tore around the corner of the ASK-9 office building, with his pack chasing after him. To a certain extent, he reverted to the flight state he had been in before when he was on the ASK-9 grounds. I called the pack back to me, and Viper followed them to us.

At first, Viper gravitated to producer Todd and location manager and dog handler Mercer from my crew, because they had represented safety to him for the past two months. Harlen was very upset. He felt that Viper didn’t recognize him or care about him anymore. I told Harlen that Viper was used to being a certain way in his old environment and that we should give him time to adjust to the new situation. It was important that we all stay calm and put no pressure on him. When Viper turned away and went toward the places where he used to hide before he came to rehab, I used the vibration collar to remind him that the safest place was back with us. I instructed Todd and Mercer to ignore him. In this way, I was passing Harlen an invisible leash.

Twelve minutes after we arrived, Viper recognized Harlen—jumping on him, licking him, celebrating their bond of affection. Harlen was incredibly emotional. “I could feel the tears forming. ’Cause that’s my boy. His whole demeanor has changed.”

So how did Viper change from a totally fearful guy at rock-bottom into a cautious but affectionate and balanced dog? I believe Viper’s insecurity had arisen from his stunted puppyhood experience, but unfortunately Harlen had tried to repair him using dog training instead of dog psychology. Anyone who knows how to train dogs to find cell phones is an exceptional dog handler, but what Harlen didn’t know was how to rehabilitate a dog that was as far gone as Viper was. My rehabilitation wasn’t based on tools, even though it was helpful to use them now and then along the way. It was based on the very foundation of the human-dog relationship—the foundation of trust.

The beautiful thing about Viper’s rehab was the help that came from everybody in my Dog Whisperer family—from the producers to the crew to my kids to my trusty pack of dogs at the Dog Psychology Center. When I followed up with Harlen and Sharron three months later, Viper was doing much better. He was going everywhere with Harlen, including outings around town and trips to the busy grocery store, and he had become much warmer toward strangers too. Harlen told me that Viper even slept near his bed now.

|

| Viper and Harlen Lambert |

The most remarkable change was that Viper had become much more balanced in his trained task. Before his rehab at the center, Viper would become nervous if anyone but Harlen was in the room with him. When the Dog Whisperer crew came back to tape him for a follow-up shoot, Viper was able to locate all eight hidden cell phones while the whole crew was right there in the room with him.

When a dog is at rock-bottom like Viper was and is able to come back and live a full and happy life, it makes me feel like there is hope in the world for all of us.

Cesar’s Rules FOR HELPING A FEARFUL DOG REGAIN BALANCE

1. Take the time to build the dog’s trust. When you first meet him, use no touch, no talk, and no eye contact. I often sit sideways with a dog, ignoring him, until he eventually gets curious and comes to me. You can’t ever clock the process of building trust, especially with a fearful dog. It takes as long as it takes.

2. Don’t feel sorry for the dog or pet him when he acts fearful. This only nurtures his fears. Instead, stay calm and assertive. Your own demeanor will tell the dog that he is in a secure situation. Once again, you may have to go through this process many times before you can influence a fearful dog with your own energy, but eventually you will.

3. A dog that is too fearful needs to learn the fun of being a dog before he needs formal “training.” Use a backyard pool, a favorite toy, a game, his best doggie friends, or food rewards to distract the dog and help him enjoy himself, even around the thing that makes him fearful.

4. Don’t invade the dog’s space too soon. Let the dog come to you and offer himself for affection before you reach down into his personal space. To avoid intimidating him, pet the dog under his chin and face instead of on top of his head.

5. Gradually expose the dog to the things he fears. Start very small, in three- to five-minute intervals, then reward after the exposure with whatever it is that the dog loves best, be that food, the pool, or a Frisbee session. Reward every tiny success. Make sure your energy is calm and centered at all times. Work up to longer sessions and more difficult challenges once the dog has mastered the shorter lessons. To make the exposure more pleasant, pair it with something the dog likes, such as treats or a favorite toy.

6. If the dog can be around other dogs that are well behaved and balanced, nothing in the world beats the power of the pack. Another dog can influence a fearful dog much faster than we humans can.

In the BASIC INSTINCTS - How Dogs Teach Us, we discuss how you can prepare your dog for all types of learning so that he becomes the obedient companion of your dreams—while retaining the natural balance and “dog-ness” that Mother Nature intended him to have.

Cesar Millan with Melissa Jo Peltier.

0 comments:

Post a Comment