|

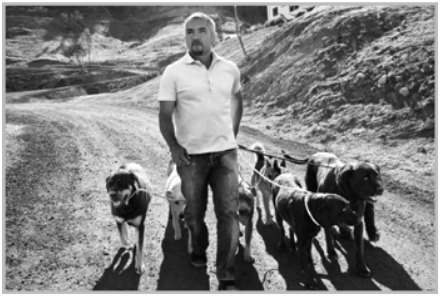

| The pack takes a walk at the new Dog Psychology Center. |

THE WALK

Anyone who watches Dog Whisperer knows how seriously I take the concept of the walk. Walking is about much more than giving your dog exercise, although exercise is the first and most important element in my three-part fulfillment formula and a big part of why we walk our dogs. To me, however, walking side by side is also the activity that forges the deepest kind of bond between human and dog. It is the primal core of that relationship. Thousands and thousands of years ago, humans and dogs first walked, hunted, and migrated together and thus became two species that would evolve side by side as interdependent partners. It’s a beautiful story—one of Mother Nature’s miracles—and when I walk with my pack of dogs in the hills behind the Santa Clarita Dog Psychology Center, I can hear thousands of years of human-dog history echoing in every step we take together.

This is why one of the first things I do when I work with a client is to make sure that he is walking his dog correctly.

Cesar’s Rules FOR MASTERING THE WALK

1. Leave and enter your house in front of your dog. Position in the pack is important.

2. Don’t let your dog leave the house in an overexcited condition—make sure she is calm-submissive and in waiting mode before you open the door. Make sure you are the one to invite her outside and to trigger the activity.

3. Walk with your dog behind you or next to you, not in front of you (though there is a time and a place for that), and definitely not pulling you or creating any tension on the leash.

4. Make your walk a minimum of thirty minutes for older, lower-energy, or smaller dogs and forty-five minutes for larger or higher-energy dogs.

5. Walk like a pack leader—head up, shoulders back. Your posture is part of the body language that your dog reads when assessing your energy. Keep your arm relaxed and the leash loose, as if you were holding a briefcase or pocketbook.

6. Alternate between the formal, structured walk and short breaks for your dog to pee, sniff, and explore, which may even include short bursts of walking ahead of you. The key is for you to be the one to start and stop the behavior.

To me, the ideal way to walk with a dog is off-leash. I love it when I walk with a pack of dogs off-leash and they all fall into formation behind me or at my side. I can’t describe what a wonderful, connected, harmonious feeling that gives me. I agree with Ian Dunbar that the off-leash experience is something all dog owners should be shooting for. But that isn’t possible for everybody, and we do live in a world of leash laws and potentially dangerous distractions. So mastering the walk on a lead, or a “walk to heel,” as it’s traditionally been called, is a crucial skill for every dog owner to develop.

THE WALK: WALKING ON A LEAD

Before taking your dog for a walk on a leash, you need to know that she is accustomed to the leash and feels comfortable wearing it. Some dogs seem not to notice the presence of a leash and collar; others exhibit fear, annoyance, and even anger at being constrained in this way. The first experience of a lead can change some dogs into bucking broncos.

If you are starting with a puppy, the solution is easy. Start the puppy young with a loose, short leash, and let her wear it during pleasant experiences such as feeding time, supervised playtime, and times when you are giving her affection. Get her used to you putting the leash on and taking it off and the sensation and the weight of the leash, so that the tool signifies nothing except happy experiences and a way for the two of you to bond. Since puppies are programmed to follow you, a leash isn’t always necessary in the first months of life, but you can keep a loose rope or nylon slip lead clipped to your belt as you walk around the house and go about your routine to help your dog build the association that a leash means “follow me.” If a leash is what a puppy knows and becomes accustomed to in her first eight months of life, then it should never be a big deal to her, even when she enters her rebellious adolescent period.

For older dogs, especially shelter dogs that may have had bad experiences with tools in the past, it’s your job to make sure that any leash you use has only positive associations. Never bring a tool to a dog—always allow the dog to come to the tool. Use a treat or a toy or something that attracts the dog, then lightly rub the leash back and forth on top of the dog’s head while she is playing or munching. Do this a few times, with no pressure. (In other words, don’t do it five minutes before you want to take your first walk!) Once the dog seems comfortable with the leash, gently place it over her head, allowing her to provide the momentum of pushing through. With an older dog that has leash aversion, you can practice what I suggested for puppies: let her do some normal, pleasurable activities with the leash on. (This goes for any tool you might want to use.)

When you start walking your dog on the leash, start with small distances in comfortable, familiar areas before you venture out for the real thing. Viper, the fearful Belgian malinois I wrote about in THE BASICS OF BALANCE - The Foundation of Training, had attached extremely negative associations to every tool that had ever been used with him, so I had to go through this routine from scratch with all the leashes and collars he feared.

The great thing about dogs is that they can let go of the past much more completely and easily than humans ever can. If you are gentle with your dog and don’t rush things, it should take only a few sessions of this type of positive conditioning for her to feel comfortable wearing the leash or collar you have chosen for her.

THE WALK: PRACTICING THE WALK

I’m not a big one for the command “heel,” since my rules for a good walk, outlined earlier, are very basic. Still, these rules must be practiced daily to become perfect. Problems that can arise on the walk range from pulling forward to wandering off to the side to sitting down and refusing to budge. Another problem that is all too common occurs when a dog becomes distracted by or even aggressive with another dog or person walking by.

I have found through my experiences with hundreds and hundreds of dogs and their owners that the owner’s attitude and state of mind often present the biggest problems on a walk. Why is it that I can take a dog that an owner insists has never been able to walk on a lead, and in five minutes I’m walking perfectly calmly and happily with her? It’s not that I’ve done anything to “fix” the dog in that five minutes. But I simply cannot imagine having a problem walking a dog. I’ve never had a problem in my life with it, so I can’t imagine failing. The dog reads my confidence in my face, my body language, and my emotional state, which she may be able to sense by smelling the tiny changes in my chemical and hormonal balance that indicate whether I am calm or nervous, happy or depressed. When owners dread a walk with their dog, the dog knows it; when owners anticipate awful events, the dog anticipates right along with them.

Beyond the psychological and spiritual aspect of the walk, there is the purely mechanical part of it. Traditionally, dogs are walked on the left-hand side. Personally, I feel you should find the side that feels right for you, teach your dog to walk on that side, and stick to it until you are certain that you and your dog are totally in sync during your walks and that controlling her comes easily. Then teach her the same routine on the other side. Thus, you’ll be able to walk her on whichever side is more convenient for a particular situation or environment. Being able to walk your dog on either side is yet another way of establishing your leadership in many different situations. The instructions in this section are based on a left-hand-side walk; reverse the instructions if you want to start on the right.

Some trainers and owners still like to use the command “heel,” so I asked my colleague Martin Deeley, executive director of the IACP, to share his advice for teaching this behavior.

THE WALK: MARTIN DEELEY’S INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE WALK

“The handle on your lead should be in your right hand, and your left hand should act as a guide for the lead down to the pup,” Martin begins.

“If you are left-handed, do this the opposite way round: handle in left hand, guide with right hand, and keep the puppy on your right-hand side. Walk slowly forward, and if she is on the left, set off on your left foot, encouraging your pup to follow—give the command ‘heel.’ If your pup enjoys being around and following you without the lead, this should be relatively easy, but be ready for a few ‘battles’ if she decides that the lead is constraining. If she runs ahead, stop and encourage her back alongside you before walking on again. If she stops, encourage her to keep up with you and to keep moving forward. If your pup likes treats, then these can help with the encouragement, but don’t let her train you to give her treats by stopping or running ahead!”

Martin offers an interesting solution to the pulling scenario. “If a pup forges ahead,” he continues, “I find that stopping, waiting for her attention, and then doing a number of 180-degree turns makes her look to me to find out what I am going to do.

“Initially I may command ‘heel’ each time I turn, but after a while I say ‘Heel’ only at the beginning or if we have stopped for a short while. The reason is, I have given a command, and when she understands it, that means to do that command until I give a different one. Also, some dogs learn to pull and then do so, waiting for the command to stop pulling and change direction. If they do not know when that change in direction is coming because you do not give a command, they are more likely to watch you and be attentive for the change of direction.”

Martin recommends practicing your walks on sidewalks or narrow country paths to provide a framework for your dog to walk in straight lines beside you.

Rehearse your about-face turns here as well, so that they become second nature.

THE WALK: TO POP OR NOT TO POP?

Some trainers don’t agree with using leash corrections on a walk. Martin and I are not among them. If a dog walks ahead of you, a quick, split-second “pop”—not a jerk but a “pop”—is a good, non-aggressive way to catch his attention. I use a leash pop, a quick touch, or a foot tap (not a kick—tap by bending the leg farthest from the dog to prevent the tap from carrying any force) in the same way I would tap my son on the shoulder in a dark, loud movie theater to get his attention to see if he wanted some popcorn.

Properly applied, a leash pop merely reminds your dog to pay attention to you. When you are first practicing the walk, you can immediately turn and go in the opposite direction after a leash pop, encouraging your dog to come with you. In this way, you are always leading and she is following.

“In training a dog to walk,” Martin says, “you go no distance unless she is alongside you. Therefore, it does not matter if you never go more than a few yards, or even get to the end of your driveway at first. After a while, your dog will realize, unless she walks on a loose leash with you, she isn’t going anywhere.

“As soon as your dog begins to walk comfortably on the lead, you can concentrate on getting the positioning right. You can use many different aids to achieve a close ‘heel.’ ” Martin suggests going along narrow country paths or walking close to the side of a wall or a fence as ideal ways to practice positioning. “With the dog between yourself and the fence, you can concentrate on keeping her from going forward or dragging backwards. As she begins to walk more with you, if she pulls forward, tap your thigh and turn sharply to the right, or do a complete about-turn so that she is behind you again.

“If your dog starts dragging behind you,” Martin continues, “tap your thigh and encourage her up to you. Increase the patterns that you make with your dog at your side by turning left and right and doing complete about-turns. If she is not concentrating, turn without warning and then tap your thigh to bring her up to it—it will encourage the dog to keep an eye on you. It may help to have two trees or posts or any objects that you can walk around and do a figure-eight path. In this way, you are turning right and turning left around these obstacles. Make sure you encourage her and make the exercises fun; being serious at this stage can create concerns. The relationship you build is the most important.”

Also vary your walking speed during these exercises—sometimes walking normally, other times fast, even trotting, followed by slow walking. Slow walking can teach your dog to pay more attention to you and to concentrate on what you are doing. Putting a lightly weighted backpack on a higher-energy dog is another way to slow the process down so that the lesson becomes clearer.

“When you stop,” Martin suggests, “ask your dog to sit.

“If the lead is held in your right hand, you can slide your left hand downwards and guide the dog’s backside to the floor as you stop and say, ‘Sit.’ It does take a bit of practice to do this well, and sometimes you will find that your dog anticipates and moves forward more quickly than your hand can push.

“A useful method of training your dog to walk correctly at heel is to have the lead in your right hand but behind your body rather than in front. Again, your left hand can guide the lead, but if your dog tends to move forward, the lead comes up against the back of your legs and their movement actually gives the dog a small pull backwards. I have also found it easier using this position to achieve the sitting when you stop. The dog cannot move forward and your left hand is relatively free, enabling it to guide the dog’s backside to the ground.”

The aim should be always to have your dog on a loose leash at any time in any place, even when there are distractions. So when you’re stopped, put your dog in a sit and keep the leash loose.

THE WALK: VARY YOUR ROUTE

Martin has one last little tip for all your walks. “Change the route you take on walks. [Your dog] will often pull more on the return to your home than leaving it. So don’t be predictable, and if she does begin to pull at any stage, about-turn and go in the opposite direction until you have her attention once more. And always work to keep the leash loose. It should hang loose when your dog is in the right position alongside your legs.”

Changing your walking route is also essential to keeping your dog interested in walking with you. Dogs love patterns—a walk at the same time every day, food at a regular hour—but they also crave adventures. If you walk the same three blocks and back every day for six months, your dog may exhibit symptoms of boredom or engage in frustrated, destructive behavior, even if you are giving her the required thirty to forty-five minutes of exercise, twice a day. Just like humans, dogs need a change of scenery now and then! The more you change your walking routines, the more exciting the challenges you offer your dog’s mind and the more you establish your leadership position with her in many different environments.

THE WALK: LEASH-FREE WALKING WITH A CLICKER

Using a clicker can help you teach a dog to heel off-leash—if you have a safe, enclosed area to practice in and a lot of patience. Kirk Turner is a dog trainer with over twenty years’ experience who uses clickers among many other techniques to train pets as well as working dogs. “The first thing to know about clicker training is that you are not ‘making’ the dog do anything,” Kirk stresses. “You are simply marking a desired behavior with a click sound and immediately supplying a motivator like food, a ball, or maybe a small squeaky toy for just a second or two. So I first figure out what is extremely motivating to a particular dog, and that will be what I use.”

Kirk gives us the example of Sparky, a miniature dachshund who is incredibly motivated by Duck Jerky treats.

“Once I’ve established my great relationship with Sparky by teaching him the relationship between the clicker and the reward, I can start walking around, and he will follow me and catch up with me. I wiggle my fingers on my left side, and when he is right there I will click and give him his treat. I change directions frequently and look at the ground about four feet straight in front of me and just notice when he comes into heel position with my peripheral vision. As he is there, I will say, ‘Heel,’ and walk a couple of steps, then click and treat. I love to start this process when the dog is off-leash. Randomize the clicks and treats as he gets better at it.”

THE WALK: TOOLS

Tools—leashes, collars, and other aids that dog owners use—are inanimate objects invented by humans to help humans handle dogs. They are neither good nor bad—they just are tools. In my opinion, it’s the energy behind the tool—that is, the attitude and state of mind of the person who’s using it—that can transform a tool that was intended for good into a device that causes a dog discomfort or fear.

If you are raising a dog from puppyhood in the manner I describe in How to Raise the Perfect Dog, you may never have any need for an advanced tool at all. Your puppy is born with a built-in leash, and if you take full advantage of that during her formative months—while establishing a firm foundation of leadership, of course!—your walks should come easily, and a simple nylon or rope slip collar or light, flat collar with a clip-on leather strap or rope should be all you ever need. Mr. President, Angel, Blizzard (aka Marley), and Junior, the four pups I raised for that book, are all adolescents now, and their respective owners—MPH Entertainment paralegal Crystal Reel, Dog Whisperer director SueAnn Fincke, Dog Psychology Center director Adriana Barnes, and myself—can take these dogs anywhere, anytime, with the most minimal leash available. Anyone can walk them, and they understand the concept that the leash means to follow. They are also all great followers in off-leash situations. Recently, I was in a busy, crowded airport with Angel, and people would stop and stare, amazed at how calm and perfectly obedient he was as he followed me through crowds and up escalators and through the security lines. This is the huge advantage of early conditioning and preventive training. If your pup never experiences anything bad about a leash, your chances of having any future problems on the walk are greatly diminished.

However, some older dogs, shelter dogs with serious issues, or dogs that are too large or powerful for their owners to control with just a slip leash may need more advanced tools, usually on a temporary basis, but sometimes for longer. Here are some of the many tools that are available to today’s dog owners.

The Flexi-Leash

Pros: The flexi-leash allows a dog to wander and explore while not being confined to one particular leash length. It lets a fearful dog have a less structured walk, which can work to build trust, while an owner slowly introduces a shorter leash over time. An example of a great use for a flexi-leash was in my strategy for building Viper’s confidence in stressful situations, encouraging him to solve his own problems without my interference (see THE BASICS OF BALANCE - The Foundation of Training).

Cons: By not providing much structure, the flexi-leash does not convey the message that the owner is in charge on the walk. An owner can end up being pulled in whatever direction the dog wants to go. The flexi-leash also offers only minimal control over a dog and should not be used with high-energy, dominant dogs.

The Choke Chain or Training Collar

Pros: Despite its negative name, there is no choking involved provided that this tool is used correctly. When a dog wanders away, the split-second tightening of the chain around the neck sends a message of correction. There is an instant release once the correction has been heeded. Its sole purpose is to get the dog’s attention and to motivate her to self-correct her behavior.

Cons: If used incorrectly, the choke chain can in fact choke a dog and cause harm. The owner should have a professional give hands-on instruction in how to properly use the choke chain.

The Martingale Collar

Pros: Designed to help a dog stay comfortable while remaining securely on the leash, this tool has a longer, wider section, usually made of leather, chain, or nylon, that is joined through two loops. The larger loop falls loosely around the dog’s neck; the smaller one is clipped onto the leash. If the dog pulls away from the leash, the tension pulls the small loop taut, tightening the larger loop around the neck. The wide section prevents the collar from becoming so tight that it cuts off the dog’s airways.

Cons: In my experience, martingales are a good alternative for happy-go-lucky dogs that don’t need a lot of correction and for dogs that are basically well behaved and just need an occasional reminder. Martingales are not as effective in dogs that are just learning to walk on a leash.

The Illusion Collar

Pros: This collar is an original design that keeps the leash at the top of the dog’s neck, which is the most sensitive area. It also gives the lower part of the neck support, while allowing the owner to correct at the more sensitive upper neck. The idea is to give the owner more control over the animal during the walk while keeping the dog’s neck safe from constriction.

Cons: I’m biased, but I love this tool as a method to teach an inexperienced owner the proper way to walk a dog. Some owners may feel, however, that the collar is too limiting for their laid-back or already well-behaved dog.

Harnesses

Pros: Harnesses were originally invented for tracking or pulling. The harness allows the dog to use the entire weight of his body as leverage. It also allows a dog more freedom, including being able to keep his nose against the ground, which is necessary for tracking.

Cons: For many dogs, the harness triggers an instant pulling reflex. I’m always surprised at the number of people who use standard harnesses on their dogs and then wonder why their dogs are so out of control on the walk. As Hollywood trainer Mark Harden puts it, “When I want to teach a movie dog to pull, I put her in a harness.”

The No-Pull Harness

Pros: Designed to gently squeeze a dog’s chest when he starts to pull, this harness causes discomfort that encourages the dog to stop pulling.

Cons: Dogs can actually still pull in this harness, but they have to contort their bodies to do so. This harness will not prevent a dog that is hard to handle from finding a way to pull.

The Halti and the Gentle Leader

Pros: Also called the head collar. Fits around the dog’s face, positioned far down the nose. When a dog pulls, the halti tightens around the dog’s mouth, and then it loosens when the dog relaxes. If a dog is too strong for you to control, the halti can give you a more direct way to keep him from pulling you around. Some people who feel uncomfortable or insecure managing a neck collar are happier with a head collar.

Cons: Some dogs feel automatically uncomfortable wearing a head collar—it’s not natural for them to have something blocking their mouths. It is also an easy device for the dog to revolt against … and win.

The Prong or “Pinch” Collar

Pros: Made up of chain or plastic links that are pointed toward the loose skin around a dog’s neck, when tightened, the prong collar gives a quick startling correction—like a bite. The idea, as with the choke chain, is for the dog to self-correct to stop the unpleasant sensation. If used properly, the prong collar should never be painful—the objective is pressure, not pain.

Cons: Repeated, violent corrections can puncture a dog’s skin, especially if the collar is not fitted correctly. If a handler is not trained in its proper usage, it can cause pain and injury.

As Ian Dunbar has shown us, there are successful techniques for working with dogs that don’t involve leash corrections. But many positive- and rewards-oriented professionals still use this method in a safe, humane manner. “As dog trainers, I think we have to be honest and try not to pigeonhole ourselves into one training camp or definition,” says Bonnie Brown-Cali. “It limits our training tools and closes us off from ideas that may help a dog. Using purely positive training techniques is almost impossible because there is always some form of correction. If a dog is being trained on a six-foot leash and runs to the end of the leash, the dog is corrected simply by the fact that he hits the end of the leash. To use purely positive techniques, the dog would have to be off-leash in a closed environment, like a dolphin in a pool, and be motivated to want to work with the handler because there is no other option. On the other hand, using purely compulsive techniques can have the adverse affect of teaching avoidance behavior. I want dogs and their people, whether it is an elderly client with a Cavalier, or a hunting dog and his handler, to be happy and confident in their work. If you pull ideas from a large bag of techniques, you have the tools to train a diverse dog population.”

“There is no nice way to deal with prey aggression,” says trainer Joel Silverman, who also prefers a positive approach whenever possible. “For people who say they can deal with prey aggression using treats and clickers, I would get them on TV and say, ‘Here’s a hundred thousand dollars. Make it work.’ Maybe they can make it work, but I don’t see them being able to teach it to somebody else. You take a high–prey aggression dog that wants nothing more than to go after somebody, and I’m very open about this. I say this at my seminars. You need to bring in specialists that deal with prey aggression or deal with aggression.”

e-Collars

The electronic collar (the e-collar, or “shock” collar, or its milder cousin the vibrating collar) is not a tool designed to aid owners on the walk, though I’d like to say a few words about the myths and realities surrounding it. First of all, it is not a device suitable for basic obedience training, and since it is a punishment-based device, it should never be used for creating or adding a new behavior. In some countries, it has become illegal because of past misuse and misunderstanding of its purpose. For the record, in 317 Dog Whisperer cases, there have been only 8 that featured e-collars. (The owners were already using the collar in 4 cases, and I simply instructed them in its proper use. In 4 other cases, I introduced the e-collar myself to solve a specific problem.) Remember also, most modern e-collars have variable settings, from vibrate (and as we’ve seen with Viper, there are collars on the market that only vibrate) to a range of higher electric stimulation that can feel like anything from a light tap to a buzzing sensation to an irritating tickle to a tense unit vibration to a sharp, static shock. The goal of the collar is not to cause the dog pain or to create fear, but to startle and redirect the animal from the activity it is engaging in by creating a negative association between that activity and the decidedly unpleasant stimulation of the collar.

Martin Deeley, who does use an e-collar in training, claims that instead of seeing it as a device to be used solely for correction or punishment, the highly variable levels of the best modern e-collars make it useful as a communication aid between human and dog, analogous to an invisible leash. “I find it a very versatile tool that can be used at low levels just barely perceptible to the dog to interrupt an unwanted behavior or guide and assist the dog’s learning, while maintaining a very happy disposition. The modern e-collar is not the correction/punishment tool of its terrible reputation—it is the off-leash communicator that many owners dream of. But it has to be introduced and used correctly, and that is where professional help is essential.”

Although those who advocate the banning of e-collars cite studies that point to the dangers of their misuse, other peer-reviewed scientific studies indicate that properly used e-collar rehabilitation can bring about quick, effective, and permanent changes in unwanted behavior without causing hurt or injury to dogs. I believe that, if employed correctly and under the right circumstances by a trained professional, an e-collar can save the life of a dog with a minimum of time and stress. However, there is no question that it is an advanced tool that can be abused or mishandled by an uneducated person.

The primary use of the e-collar is to block prey drive. Hardwired into a dog, prey drive can cause a dog to try to chase rattlesnakes, herd cars in the middle of traffic, or sprint after a jogger into a dangerous street. In a recent NPR interview, Temple Grandin, the esteemed advocate for the humane treatment of all animals and a champion of positive reinforcement, describes what she considers the correct use of an e-collar. “Car chasing, jogger chasing, cat killing, deer chasing—anything that’s prey-drive behavior. And this is not aggression and it’s not fear. It’s a very special other kind of emotion that the animal has,” Grandin explains. “And you’d want to put the collar on, have the dog wear it for two days, and then—because you never want him to find out that the collar did it—and then one day a thunderbolt from the sky blasts him for chasing deer. And that’s one of the few situations I would use a punishment.”

San Francisco Bay Area trainer Kirk Turner, who uses primarily positive reinforcement and clicker techniques in his work, has used e-collars to protect coursing dogs and keep them safe. “When you send a coursing Borzoi team out after a rabbit, if that rabbit goes through a barbed-wire fence, then that Borzoi wants to go through that barbed-wire fence to get that rabbit,” Kirk warns. “There, an e-collar is a totally appropriate use. Every tool I have used on dogs I have tried on myself. I’ve put on an e-collar, I’ve shocked myself, so I do know what a level-five charge on a Tri-Tronics e-collar feels like. I have also used the vibrate setting to teach deaf dogs. You use the vibrate setting to get their attention and then use hand signals for everything else.”

I don’t recommend that anyone ever use an e-collar—or any other advanced tool, such as the prong collar or choke chain, for that matter—without thorough instruction from a qualified professional in the proper use of the device. For instance, Bonnie Brown-Cali teaches classes in the ethical use of correction-based tools, including the e-collar.

According to Katenna Jones of the American Humane Association, the AHA is very stringent in its guidelines for correct use of an e-collar and recommends its use only in the following cases:

• When employed by a professional who is highly educated in animal learning theory

• When employed by a professional who is highly experienced with the tool or technique

• In very rare, exceptional, life-or-death situations

• As a last resort when all other options have been exhausted

• For three or fewer trials (more than three trials or presentations borders on abuse and should end immediately)

THE WALK: WALKING WITH A CHOKE COLLAR

I find the choke chain to be a practical tool, but I almost never use it unless a client is already using it and has become comfortable with it already. In 317 Dog Whisperer cases, I’ve introduced the tool myself only one time, because my goal is a closer connection between human and dog, leading toward the concept of an off-leash experience. I prefer a simple, light leash placed high up on the neck to give me more control, as you see done by handlers working in a dog show. But many slightly built women and men are more comfortable with a choke chain, which can build their confidence when handling a powerful or high-energy dog. Moreover, a number of the professionals I interviewed for this book consider it a useful device to use in training, especially with adult dogs that have had no previous experience walking on a lead or following a human leader.

“I’m very open about the fact that I use a choke collar in some situations,” says veteran trainer Joel Silverman. “And you know what? I’ve never had one person, not one person in thirty-five years, ever come up to me or ever write or e-mail me and say, ‘I have an issue with the way you use it.’ I mean, they may say, ‘I prefer not to use a chain collar,’ which is totally cool, but the point is, it’s not about the tool, it’s about the way you’re using it.”

Working with his Anatolian shepherd Oscar, Hollywood trainer Mark Harden showed me how he uses the choke chain during a walk. When used correctly, the metal choke chain, in Mark’s opinion, is more humane than a cloth leash. “The thing is, it’s there and it’s gone. Whereas [with] a cloth collar, there’s always something, there’s always sensation there that they’re feeling, and they can’t pull or unpull, it’s always there. So there’s not that instant of difference. The other thing is, they have a pull instinct. They get their head stuck in something, and their instinct is to pull out of it. So you can nag them with that all the time and never make an impact, and it seems to me the people I see using straight cloth collars nag their dogs a lot more as opposed to going ‘boom,’ over, taught, let’s go on with our day.”

Mark brought Oscar close to show me the correct way to put on the collar. “So as you face the dog, it should look like a ‘P,’ ” Mark said, holding the chain out in front of the dog’s face. “And it goes over him.” He slipped the collar over Oscar’s head. “And then when it’s applied, it releases.

“The first thing I do when I get an animal I need to train for a movie is, I’ll go for days, hours, hours, hours, just walking.” Mark led Oscar around the sheepherding field where we were working. “I’m saying to the dog, ‘You walk the way I walk.’ And I believe that all the control that I have and all the relationship I have flows through this leash. If I can get you walking, I can get you doing anything.

“There’s no force. I don’t pull at all. I mean, I couldn’t pull this dog. This dog could pull me anywhere he wants to go,” Mark said. “Oscar is like a 160-pound four-wheel-drive vehicle.” It wasn’t the leash or collar that gave Mark such control over the enormous dog. It was the leadership and trust he had worked to build into his relationship with Oscar.

“To me the biggest mistake people make is there should never ever, never one second, be tension on this leash except for that split second that I want to communicate with him. The rest of the time it’s loose.

“I see people on their walks, and it’s always like this.” Mark balled the leash up in his hand, causing tension on Oscar’s choke chain. “If my leash is always loose, I never have to say anything. I don’t say, ‘Heel’; I don’t yell; I don’t do anything. I just walk.”

Mark continued to walk, and as soon as he didn’t have Oscar’s attention, he turned around and walked the other way, giving a little tug of correction. Oscar followed right behind him. Mark did this several times.

“I keep changing directions because I’m not as interested in having him stay right by my side, but I want him to check in. It’s like, ‘You don’t know where I’m going, Oscar. How can you be in front of me?’ So what I do is, it’s a pop, boom, instant, so his own weight works against him.”

Mark believes that the problem with choke chains lies in owners who don’t know how to use them. “To me, there’s no better way to teach my dog and to control him than this. It’s easier, it’s faster, it’s not as constantly nagging as a cloth collar,” he said. “This is a quick communicator, and one day, fifteen minutes, and I’ve got a dog that walks with me as if he was mine his entire life. People look at it like it’s magic, but people aren’t taught to use it properly.”

Even though he himself gets great results using choke chains, he also knows that owners need to find what works for them. “If you can make a cloth collar work for you, if you can make a harness work for you, there’s no judgment. I’ve trained hundreds of dogs—this is what works best for me. I’ve never hurt a dog with it. I mean, I can cut my vegetables with a knife, and I can stab somebody with a knife. It’s the way it’s used, it’s not the tool itself.”

Katenna Jones, an applied animal behaviorist in the Office of Humane Education for the American Humane Association, has a very different opinion about chain collars. “I’ve never used one in my life and never will. Do they work? Certainly. But are they the most ‘humane’ tool out there? No way. If I came to a client that was using one, I told them if they wanted to work with me, the choke chain goes. I primarily train, especially reactive dogs, on head halters.”

However, even more benign tools, like head halters, can be misused by an uneducated or impatient, frustrated owner. “I see people all the time jerking on a Gentle Leader like it was a choke chain,” warns Kirk Turner. “And I can just imagine what it’s doing to that dog’s neck. The problem with the Gentle Leader, as with most tools, is that the dog knows when it’s on and knows when it’s not. Personally, I’d rather accomplish what needs to be accomplished with my nonverbal signals, such as the blocking technique and a calm, assertive attitude.”

THE WALK: COMING WHEN CALLED

As our survey in THE BASICS OF BALANCE - The Foundation of Training shows, the number one most important thing for pet owners is having a dog that comes when called. Nothing is more maddening to most people than a dog that ignores them and only comes when she feels like it. In many cases, a frustrated owner will reprimand a dog after she does return. Dogs live in a world of cause and effect, so that pet has no clue why she is being yelled at. Now you have taught her that there is a negative association with coming in to your call. Next time she’ll be even more likely to play “keep away” when you call her to you. Catching a dog you’ve lost your temper with is not easy and makes you even madder, which further damages the bond between you and your dog. Thus, owners get caught in a downward spiral.

A dog that won’t come can be a danger as well. If you call your dog in a dangerous public situation near a road or other potential accident area, your panic, fear, anger, or other negative emotions may spill out through your voice, and you will give your dog more good reasons not to want to come to you, even when you know you’re calling your dog for her own good.

“There are many reasons a dog wants to come back to you,” says Martin Deeley. “This can be broken down into two basic emotions. The first, because she wants to, and the second, because she feels she has to. She hears the leash being taken from the hook for a walk, the food going into her bowl, and abracadabra—the magic recall with tail wagging. Or she hears you call and knows, ‘I had better go because if I don’t there will be consequences.’ Sometimes it is a little bit of both.”

Consistent recall is built on the relationship you have with your dog, the leadership qualities you possess, the pleasures and rewards you provide, the limits and boundaries you have set, the consequences for your dog of not doing as asked, and, most important of all, your dog’s innate desire to be with you—to be part of your team and your pack.

In How to Raise the Perfect Dog, I explained that raising a dog from early puppyhood provides you with an invisible leash, because all puppies are programmed to follow. Once they are separated from their mother and their littermates, they will transfer that instinct over to you, their new pack leader. The first step in creating a dog that will come to you every time is to utilize those precious first eight months of her life to develop and strengthen that invisible bond between you. One of the biggest mistakes owners make that contributes to poor recall is allowing a young pup too much freedom early on. You naturally want your dog to have times of play when you give her free rein, but while your puppy is young, “freedom” means more than just romping around in the yard. It also means being comfortable and secure knowing what the rules and guidelines of your pack are going to be and knowing that she can always trust you to keep her safe and let her know what she’s supposed to do. While she’s young, concentrate on conditioning your puppy to believe that the very best, most satisfying things in her life happen when she’s with you—not when she’s out on her own sniffing in the grass or interacting with another dog.

When you inadvertently teach your dog that her independent wandering is part of the pack “culture,” then you have put coming when you call low on her list of priorities. Then your increasing frustration with her for not coming starts to show in your body language and energy. Now you’re reinforcing her belief that it’s definitely more pleasant to be away from you than close to you.

Martin Deeley knows retrieving dogs backwards and forwards. He has discovered that playing fetch with a puppy or a young dog is a great way to encourage outdoor play and exercise while keeping the “fun” associated with you. “If you encourage retrieving a thrown toy back to you, this will also provide the opportunity to let your dog run long distances, yet remain under control as she concentrates on the ‘job.’ To begin to create a name recall, say your puppy’s name after she retrieves the toy and right when she starts back to you. Reward her with affection when she gets there. Never grab for the toy or snatch it from her in any way. Allow her to come to you and share it with you before gently taking it.”

I always advise my clients to begin the ritual of the walk when a puppy is young, but veterinarians warn that long walks are not always good for puppies’ bone development. Short walks combined with other play sessions with you can become part of the training process. “Long walks are not essential for young puppies if you use retrieving and other vigorous fun games for exercise and training,” says Martin Deeley. “Exercise while training. Your dog will get as much exercise running around close to you as she does at a distance. Once your walks become longer, make your structured walk a training walk. Teach her to walk on a loose leash, sit when crossing a road, sit when meeting people, and generally be a good citizen when out on public view.”

I always warn my clients that puppies are people magnets and may draw unwanted attention that will distract from your training. With both puppies and adult dogs, make sure you set limits for when people are and are not allowed to shower your dog with affection so that the structure of your walks and training time remains intact.

Until you are sure of a reliable recall, Martin Deeley advises, use a long leash or a long line so that you are always in touch with your dog. “This can be a strong ribbon type to start with,” says Martin. “And then you can reduce it to a lighter line as you trust her more. The aim is to gradually remove it in small stages while she continues to obey. Take her out for a little walk around the yard or field and let her follow, tail a-wagging, around your ankles.”

When your dog starts drifting away from you, use that as an opportunity to strengthen your ability to call her back. Turn in the opposite direction and call her, praising her as she returns. Very quickly your dog will begin to realize that if she goes too far, you will start to disappear. This will encourage her to keep at least one eye on what you are doing at all times. Occasionally, if the environment is a very secure one, if she happens to wander down one path, you can veer off on another, then call her to you. All these exercises reaffirm the importance of her coming to her name and heeding the recall command if she wants to find you again.

Hide-and-seek exercises are the next step in building your reliable recall. Hide behind a tree or lie down in the grass, call her, and then make a big fuss when she finds you.

Even with this foundation, some dogs still give in to the temptation to run away and explore. Shelter dogs adopted as adults have often become used to self-reliance and need to be reconditioned to understand that coming to you is an important and pleasurable activity.

“The most obvious way to have a dog returning to you,” says Martin Deeley, “is for the treat reward. Always put your pup in a position where she cannot do wrong; therefore, a leash or long line is very helpful to provide control. With this attached, initially back away and call her up to you, with a light, fun voice. I use ‘Here’ and make myself interesting by lowering my body a little, semi-crouching or going down on one knee [not bending over], and smiling.

“When she comes up to you, give her a very small piece of a treat she enjoys. Go back to walking. Back away again, and once more call up and treat. Make it a fun game. Begin to walk around with her on the long leash. Let her go away from you, and when she is not looking, change direction so that you are moving away from her. As you do this, call her and once more make yourself interesting and fun and offer the treat. If she does not at first respond, the moment you move away and she feels the leash she will generally want to follow you.”

As Ian Dunbar has shown us, when using treats as lures, it’s important to phase them out of the training as soon as possible. You never want a snack to become the only reason your dog comes to you. Once she is responding regularly, begin to give her the treat at random intervals. The aim is to reduce the treat-giving to none at all so that she happily comes to you even when there’s no food present. Also, many dogs, like Junior, are simply not treat-motivated. “With some dogs, you will find the ‘want to return’ is related to other rewards than food,” Martin tells us. “Retrieving or a tugger toy are examples, where your dog enjoys the game more than anything else and sees being with you as the place it all happens. In this case she comes willingly to partner with you.” If you do use a tugger or ball, teach your dog to let go or drop it in your hand when asked. You start the game and you stop the game—that is what leaders do.

As your dog learns, allow her to go farther away from you on the long line and then call her up.

This is important because a dog that will recall at five yards will not always recall at ten. Once you’ve got this behavior down pat in a safe training scenario, you can begin to introduce distractions at a distance—other dogs and people walking by, cars, cats, and other interesting things in the environment. The leash will enable you to stop her doing the incorrect action and guide her into the right one. “You may occasionally have to give her a pop on the leash to get her attention back and ensure she follows, rather than giving way to temptation,” Martin reminds us. “When you do this, never do it harshly. It is a sharp wrist-popping action or a short pull at the level of the dog’s shoulders and neck. With some dogs, just standing on the long line so she cannot move away is enough. Encourage her to you and praise her when she does come. Read your dog.

“Next,” Martin continues, “we can begin to make the leash control less by allowing it to run on the ground. Follow this by replacing a heavier leash with a lighter-weight one. Once you are successful with this, in a safe area you can shorten the leash until you take it off altogether and work your dog on the recall with no leash and no treat at all.”

If you agree with Ian Dunbar’s theory that a leash is a crutch that is often too hard a habit to break, you can follow his prescription of practicing the recall-sit, first in an area as small as a bathroom, then the kitchen, then the living room, then your fenced backyard, until your recall is solid at least 95 percent of the time. Your voice and your connection with your dog become the invisible leash in this method.

COMING WHEN CALLED—THE CLICKER WAY

Using a clicker is another way to teach the recall command off-leash. I asked Kirk Turner to outline a clicker method for teaching a recall.

“I’m working with Sparky, the dachshund, and I know he’s motivated by Duck Jerky. So I say his name, he looks at me. Click! Treat! Walk away and ignore him,” Kirk explains. “Actually, I try to avoid him. He tries hard to get my attention, but I just wait until he is distracted by something else, and then I say, ‘Sparky!’ And he looks at me and comes running. When he is about halfway to me, I click with the clicker behind my back and give him a treat when he gets to me. I also am very exuberant with my praise.

“I repeat this process several times before I use the word come. When I am positive he is going to come to me anyway, I will start saying the word every time. I will also start randomly clicking only when he is all the way to me, and I will vary the amount of treats he gets and the length of time I am praising him. As time goes by I will bring him to more distracting environments and repeat this process, maybe even from the beginning if he is too distracted.”

All these techniques are great starting points for making sure your dog comes to you when called. The bottom line, however, is that your dog must trust you, want to be with you, and respect your leadership in all environments and situations. With a puppy, this is a piece of cake; with some rescued dogs, it can take a lot of time and patience. But patience is the key. No dog is attracted to frustrated, angry, or impatient energy. If you are having a hard time getting your dog to come, check your own attitude first. Are you offering your dog something wonderful to come home to? It’s up to you, not only to establish leadership at home but to be the best thing in your dog’s life, wherever you go together.

THE SIT

All dogs can sit and obviously do it all the time on their own. Teaching them to sit on command is just a matter of capturing that behavior and attaching a word to it. This should come easily, but some people do find the timing of attaching the command to the behavior difficult. “Too often pups are told to ‘sit’ when they are doing something naughty, and owners yell the command in anger to get them to stop,” says Martin. “Unfortunately, ‘sit’ then becomes a word associated with a correction.” We want our dogs to have a positive association with this behavior.

There are many ways to teach the sit command. Remember, when you first begin teaching any behavior, start with lessons that are short and sweet and work in an environment where there are as few distractions as possible.

THE SIT: THE NATURAL WAY

As Bob Bailey points out, the simplest way to tell any animal what behavior you want from her is to simply “capture” the behavior that the animal is naturally doing, then reward it. This takes patience, but in my opinion it is the method of training that is the closest to how dogs would learn from each other in nature. Animals learn by trial and error—but when it comes to survival in the wild, there’s not much room for error. You can take advantage of this natural method and simply look for opportunities to teach many commands.

Your dog will sit on her own many times during the day. Sometimes if she is on the leash and you just stand and wait at the door, she will sit after a while. Whenever you see her moving into a sit position, say, “Sit.” Do it calmly, with a natural voice and with a smile. Send her your proud and loving energy, reward or praise her immediately afterward, and you will be surprised how quickly she can learn many commands from just doing them herself. I find myself teaching my pack all the time by just encouraging good behavior with my happiness or disagreeing with unwanted behavior by using the “tssst” sound. Dogs were born to learn, and they are hardwired to learn from us. When you use Mother Nature’s method to communicate with your dog, you may be surprised at how effortless and fun basic command training can be.

THE SIT: FEED TIME AS MOTIVATION

With a small puppy, feed time is a great opportunity to get the point of “sit” across without having to do very much, and with a built-in reward attached. First, prepare the dinner, then bring the pup to where you are going to feed.

Initially, you may let the puppy smell the food, but then hold it up away from her and wait. She may jump around at first, and she’ll probably jump on you. If so, indicate your disapproval with your attitude and body language and slowly move yourself back or to one side … and then wait.

Remember, your patience as an owner now will pay off in a well-behaved dog for a lifetime.

After a while, your pup will probably begin to try to figure out what she needs to do to get her dinner. That “figuring it out” look will appear on her face, and she will lower her butt to the floor.

At that precise moment, put the food down in front of her. “After doing this once or twice,” says Martin, “I find that the moment I go in with the food and wait, the pup sits automatically.” Once you begin cueing the sit behavior with the food ritual, just add the word sit so that the pup hears this request the split second before she sits. This way, it becomes a cue.

Praise can be your secondary reinforcer. Don’t overpraise with excitement, but feel your own pride and calmly tell her, “Good.” This way, your pup has learned the command by association and, perhaps just as important, by a behavior that she has figured out for herself.

THE SIT: USING TREATS TO LURE

Choose a treat that your dog will enjoy. The rule of thumb I use for treats is to save the best, most delectable treats for last, to reengage your dog if she begins to lose interest in the training session. I like to save a piece of chicken or a hot dog just in case attention wanes. For early in the session, or for shorter sessions, kibble or treats made specifically for training work just fine. “I prefer to use kibble that my dog has at dinnertime,” Martin Deeley says, adding, “and cut back on the amount when feeding if we have used it for training.” Obviously, using treats to train a behavior won’t work as well right after your dog has had a full meal as they will between meals. Some professional trainers like Mark Harden use their dog’s “pay” as their whole diet on working days, so the dog is literally working for her living.

You can teach this technique off or on a leash. Hold a food treat in your hand between the first two fingers and the thumb.

Let your dog sniff so that she knows it is there, and remember my rule: nose first, then eyes, then ears! When you engage your dog’s nose, you are appealing to the most important part of her brain.

Next, as she is sniffing and getting interested, slowly lift the treat above nose height and move it gradually over her head and slightly back toward her shoulders. The aim is for your pup to lift her head up, move her shoulders back, and naturally have her butt lower to the floor.

Lift the treat slowly and easily so that your dog’s nose follows it in your hand. If she jumps at your hand, take it away. Next time, have the treat hand closer to her head. The moment she begins to follow the treat with her nose and eyes and her butt begins to move to the floor, say, “Sit,” calmly and easily. “Use a natural voice,” Martin reiterates. “We don’t want to distract, startle, or concern her.” Remember one of my cardinal rules for training: don’t overexcite your dog, so that she loses the lesson in all the commotion! As we saw from my session at the Dunbars’, the movement of your hands and body also provide a visual cue in addition to the verbal “sit.” In the future, by lifting your hand in this manner in front of her head, you can signal her to sit.

“Learning words is not the way dogs are born to communicate,” says Ian Dunbar. “Dogs are used to watching people. And they’re so good at reading a person’s body language that they pick up the hand signals in every single intention. Most people aren’t even aware of their body language when they’re giving commands, then get frustrated when their dog answers to what the body language is saying, not what the command is saying.” So make sure your body and your words are exactly in alignment so that your dog doesn’t get mixed messages.

Unlike many trainers, I prefer silence to commands when communicating with my dogs. To me, training is usually based on sounds, but dog psychology is best accomplished with silence, then simple, basic sounds. After my dogs learn from my body language and hand signals, I add verbal commands only if need be. If your dog is across the field or has her back turned to you, you’re very likely to prefer that she be able to obey a range of commands expressed in human words. As we learned in our session with Ian Dunbar, the language of the words doesn’t matter. It’s the association of the word with the required behavior that counts, and the reliability with which the dog follows your commands. Whatever method you choose to teach the sit, make sure you practice it in as many locations and situations as possible, so that your dog knows what the word means everywhere she goes.

THE SIT: GUIDE YOUR DOG USING YOUR HANDS

Using gentle physical guidance is another way to show a dog the behavior you wish him to display. Once again, I like to have a dog figure out for himself what it is that I want, because I believe the lesson has more meaning for him that way. But if that approach doesn’t work for you, there’s no harm in communicating with your hands, as long as you are tender and respectful. Remember, know your dog before you train, and make sure your dog is telling you with his energy and body language that the way you are touching is okay with him. “I enjoy sitting on the floor with a small pup and having her in close to my body,” says Martin Deeley. “My hands should always be friendly. I like to get the pup familiar with a gentle touch and guidance.” He adds, “I especially want pups to get familiar with every part of their body being touched so that in future they can be groomed, nails can be clipped, and the vets can check everything out.”

Sit or kneel on the floor and let your pup come into your body. Don’t grab or force, but wiggle your fingers and encourage him to come in closer to be gently held and slowly petted. While doing this, with one hand rub on the chest and slowly move up under the chin. Slowly move your other hand down the back of the pup and apply light pressure to the butt, your middle finger and thumb resting on each hip, palm on his rear.

Gently apply pressure. Nothing hard! Once your pup makes even the smallest movement toward the floor, release the pressure immediately. Do this until you can apply light constant pressure and the pup’s butt touches the floor. While there, gradually stroke down his back, praising calmly, “Good.”

Next, add the word sit as you begin to do this exercise. Timing is essential—the word sit should precede the action you ask for. So say the word at the very moment the pup begins to move toward the floor. With just a few days of practice, you will find your pup understanding the verbal command and responding to the sit you ask for. Again, praise calmly with your happy energy or a word you choose, such as “good.”

Some dogs have a physical frame that makes it difficult to sit—greyhounds, for instance, are renowned for this problem. If this is the case with your dog, you can show her gently how to bend her rear legs to get into a sit. With your dog on a leash, kneel down next to her. Hold the leash up with one hand; if she is large, just holding her up at the front with her collar under her chin will suffice. Now run your other hand down along her back. This time, keeping your hand on her body, go past the butt, bending her tail slowly downward, and run your hand down the rear of her legs until you reach the back of her knees. Once your hand is in this position behind her knees, gently begin to move those knees inward to have them bend. This action brings her butt down. Don’t expect her to sit the full distance immediately—stop and calmly praise when you achieve small successes in the dropping of the rear to the ground. Build up the distance she descends toward the floor in small stages, until you and she are successful. Then praise her—“Good dog”—and smile.

If you have any doubts at all about your dog’s physical range of motion or any disabilities she might have, check with your vet first and have him or her talk you through this exercise to make sure you are doing it correctly. With this method, your face is close to the dog’s mouth, so always be sure of the temperament of your dog. If she is liable to nip at you, do not use this approach, Martin warns.

THE SIT: USING A LEASH

In some ways, I agree with Ian Dunbar that a leash can unintentionally become a “crutch” that is hard to give up if you establish it as the basis for your relationship with your dog. After all, I grew up with the free-roaming packs of dogs on my grandfather’s farm and didn’t know the purpose of a leash for a dog during most of my early childhood. My long-term goal is always for you to have the ultimate bond with your dog, and that includes enjoying an off-leash relationship wherever it’s safe and legal.

However, we do live in a leash-oriented society, and having a leash and collar on your dog allows you a certain amount of control that many people feel they need in the early days of training. Personally, I do not mind any type of collar, provided it is used correctly and without harshness. What works best for me is a simple leather show leash attached to a collar, or even what I call my thirty-five-cent leash—just a rope or nylon with a loose loop on the end. Martin Deeley prefers a rope slip leash or a slip chain.

Walk slowly with your dog and choreograph your movements so that she comes to a stop and stands along your left side.

With the leash in your right hand, gradually apply an upward pressure by lifting the leash, creating an upward pull. Don’t jerk the leash! Just lift upward with a gentle constant pressure. The moment her butt goes to the floor, the upward pressure is released and the leash goes slack.

Some dogs sit automatically in response to this pressure. If your dog does not, put your left hand on her back just behind the shoulders and slide it slowly down to her butt area. Now, with your middle finger and thumb straddling the spine, palm on her back, exert a little downward pressure. Again—don’t push! Just apply pressure down and slightly backward. Be firm but gentle. Through this action, you are lifting the head with the leash. “Make sure you have the leash the right length and are not overreaching yourself,” says Martin.

The moment your dog puts her rear to the floor, loosen the leash, releasing the upward pull. Repeat your praise and rewards. Once your dog is going into a sit the moment she feels the leash being lifted, add the command “sit” just before you begin to lift the leash.

Gradually, your dog will learn “sit” and know that a slight lift of the leash means “sit.” The command prompts the behavior, and soon she will also begin to learn that the change in weight of the clips fastening the leash to the collar means a “sit” is coming. She will begin to read the subtle leash signals coming from you, just as a horse does with the reins used by a rider. This kind of micro-control can make communicating with your dog during your walks much easier.

THE SIT: USING THE CLICKER

Kirk Turner continues the saga of Sparky the miniature dachshund that he successfully taught to come using a clicker and a piece of Duck Jerky. Since Sparky now associates the click with a forthcoming piece of jerky, teaching the sit command comes naturally. “Now, when I call Sparky, he comes running and sits waiting for his click and treat. I just wait until he offers the sit behavior. As I see him sitting, I bring in the word sit. Very quickly, it becomes a conditioned response. I just walk around avoiding him, and he makes sure he gets in front of me, and I will say, ‘Sit,’ and I wait until his hind end hits the floor, and that’s when I click and give the little guy a treat. Again, I will only occasionally actually use the clicker and treat, moving to only praise.”

Like all the methods outlined in this section, the clicker method works best with repeated sessions, repetition, and patience.

THE DOWN

The down command is a really useful exercise for your dog to master. It puts her into what I call a calm-submissive posture, where she can relax and watch the world go by. It’s a way to get a dog to “chill out” in any situation.

My pit bull Daddy was a master of the self-imposed down—it wasn’t anything that I taught him. When he was with me and we were in a waiting mode, he’d lie down flat on the ground next to me—front legs splayed forward, rear legs to the back. Of course, as he got older he got into this position a lot more often, just because he tired more easily. Daddy raised my now two-and-a-half-year-old pit bull Junior, who picked up the position by copying Daddy. Imitation is one of the most important ways dogs learn. Today Junior plops down next to me in the same position that Daddy used to assume. Junior is so in tune with me that he automatically understands when we are in waiting mode, just by sensing my energy. He learned from Daddy, “When Cesar is in this state, this is when we rest.” Of course, Junior is an adolescent and usually prefers a little more action, but teaching patience to a dog is a mental exercise for them too. The patience that Junior learned by watching Daddy—and that I am still teaching him to practice every day of his life—has helped me to create a new generation of mellow, obedient pit bulls as role models.

For the most part, I have found that lying down is not the most natural behavior for dogs to do on command, since they usually assume that position only when they are tired, not when they are alert. It doesn’t always make sense right away when a human asks them to do it. This was the hardest position for Junior to get into in his first session with Ian Dunbar. When I teach this behavior, as I did with Angel the miniature schnauzer in How to Raise the Perfect Dog, I like to give myself a lot of time, and I try not to expect too much right away.

|

| Daddy in the “splay” position |

For Martin Deeley, who trains both companion and hunting dogs, being able to get a reliable “down” command is important when he needs his dogs to be in waiting mode. He says of the down: “I see this as being a three-stage exercise. The first part is to teach the dog the command so he understands what it means; the second part is to have him do it without a food reward; and the last stage is to ask him to stay there until released from this position.

“Food is the obvious way with most dogs that are food-oriented,” says Martin. “However, even with food, I prefer to have an older dog on a leash so that he cannot just ignore me and walk away—plus it indicates a little control to the dog. He should know what the leash means by now, and he should know the ‘sit’ command. With puppies that are more likely to want to be with you and when you can be in an enclosed area, you can do the ‘sit,’ ‘down,’ and ‘stand’ with food without the leash. Puppies are usually a lot easier than an older dog that has not learned these commands yet.”

Ian Dunbar, on the other hand, never trains the down with a leash. He teaches it off-leash, with the sit and stand command in rapid sequence, as we saw in LOSING THE LEASH - Dr. Ian Dunbar and Hands-Off Dog Training. Using a food lure, then quickly phasing it out, is what works best for him.

“Physical prompting with hands or leash is very slow because the dog pays selective attention to the physical contact and thus simply doesn’t hear the verbal instructions. Also, hands-on and leash prompts are very difficult to phase out to get off-leash control,” Ian argues. “Clicker training is also slow, since only one behavior is taught at a time. However, lure/reward training with food or toys is lightning fast, and it’s much easier to phase out the lures and the rewards, so that playing the game becomes the reward. And so why not teach a bunch of commands at once? When I start off with a puppy/dog, I generally teach eight behaviors at once: come here, sit, lie down, sit up, stand, down from the stand, stand up from the down, and roll over.”

As for me, I like to use training tables to teach dogs specific behaviors, because it gives them a limited area to work in—they can’t “cheat” by walking away, it keeps them focused on me without any distractions, and it allows me to be at their eye level without hurting my back or my knees. Remember, dogs don’t just read our body postures—they read our eyes, our facial expressions, and even our micro-expressions, so being able to search our faces for feedback is an important way dogs figure out whether or not they’re doing what we want.

I’ve found tables to be great tools for teaching many things, but especially the down, because I can easily get down to the dog’s eye level in the beginning. Mark Harden uses tables to teach his acting dogs the army crawl, which is a “modified” version of the down. A table is also a sort of middle ground between leash-based and off-leash training. The table itself is a leash, but there is no need for physical interaction with the dog, who is figuring out the behavior for herself.

|

| Cesar trains Angel. |

Of course, it’s up to you to choose the method that works best for both you and your dog.

To begin, have a little finger-size treat in your hand. Let your dog smell it so that she knows it is there and then ask her to sit. With your fingers holding the food just in front of her nose, slowly drop your fingers down in front of her chest to between her front feet. Allow her nose and head to follow your fingers down.

When her nose is close to the floor and your fingers are resting on the floor, slowly bring them forward away from your dog so that her front legs begin to walk gradually forward. Do this until she is in a down position, then praise her and give her the treat. If she gets up before going down, try again and move your hand more slowly. Do not give her the treat if she gets up. Remember Mark Harden’s rule—reward the behavior you want, not an unfinished attempt at the behavior. Her whole body must be on the floor.

Martin Deeley offers a great trick that can help if you are working on a floor. “Sit on the floor and have one of your legs crooked with the knee in the air. Then you lure her into the down by guiding her under your legs and she sees the knee as something to put her head under.”

Remember what happened when I visited Ian Dunbar? Junior moved like molasses when food was used as a lure to teach him the down, but he hit the floor like a wrestler when Ian substituted the ball as a lure. If what you’re using to get your dog’s attention doesn’t turn her on, keep trying until you find the right reward. For some dogs, just the challenge itself—or your happy, positive energy—is reward enough. Most puppies, however, respond well to small treats.

There are other actions that can help you achieve success and move toward the second stage of the command training. One way is to rest your free hand on the dog’s shoulder blades and exert a light downward pressure. With your fingertips between her shoulder blades, rocking gradually and lightly pushing down can help her get the idea if she is slow to catch on. Once she is down, you can use this hand also to hold her there lightly for a few seconds. Reward or praise her when she does it.

If you like to work with a leash, you can place both fingers in between your dog’s shoulder blades and the leash, then use a very light downward motion on the leash to communicate the direction you want the dog to go.

It’s important that the tug be light and subtle—it is directional only, not coercive. The goal at this stage is for the dog to follow the treat. Too much pressure and she will resist it and forget the treat. By using your hands and leash in this way, you are gently reinforcing the command, and eventually you’ll be able to prompt the movement without food.

When your dog is doing a reliable down on command, the next step is to phase out the treats. Start with intermittent reinforcement—ask for two or three repetitions before she gets her reward. Then, saying the down command before she begins, use just the lightest leash tug or the finger pressure to guide her into position.

“One way I have been successful with dogs that are not interested in food,” Martin Deeley suggests, “is to put the leash under your foot so it runs in the gap between sole and heel. Then, as you pull upwards or walk while standing on the leash, moving closer to the dog’s collar in small stages, gradually the dog learns the most comfortable position is on the ground. And don’t forget that you can also use a different reward, such as a tennis ball, just like you would a treat.”

As I’ve said before, for me it’s ideal when the dog finds the position on her own and then I reward it. But people like Hollywood animal trainers do not always have the time to wait for a dog to figure out “down” on their own, in which case a light pressure or leash tug will do the trick.

Either way, your dog isn’t going to learn anything if it’s not interesting or pleasant for her to do so. If you and your dog are in sync, communicate well, and understand the nuances of one another’s body language, you’ll know right away if your dog finds something fun and is motivated or if she’s unhappy and is only doing the behavior to get you off her back. Always check your own energy. Do you feel confident and at ease with what you are doing? Or are you forcing it? Are you getting annoyed at your dog because she is taking a long time to figure this out or find the position that’s comfortable for her body? If this is the case, look for a command that your dog can do perfectly—it may be the simple “sit”—and always end the session on a high note. Then regroup, take a break, and try again later. Training should be fun, not frustrating, for both dog and human in order for it to work.

The third stage of this command is for your dog to learn how to go down on command alone and to stay there. Don’t move to this stage until you are absolutely sure your dog knows that the command “down”—or whatever signal, verbal or physical, you are using—means to lie down. Martin Deeley often does this with a leash, and Ian Dunbar always works without one, but the universal similarity between both off- and on-leash methods is consistent follow-through. Also, don’t put a clock on your dog if learning “down” is slow going for her at first—every trainer I’ve spoken to says this is a behavior any dog can master, so be as patient as necessary.

“With your dog in the sit position in front of you,” says Martin, “ask her to ‘down,’ and with your hand that held the food or pulled the leash to the floor, mime the physical motion of this action in front of her. Your hand moves from your waist and pushes down almost to the floor. Exaggerate the movement at first.”

Remember, your dog is always trying to read your body language. Watch her reaction, and the moment she makes the decision to begin going down, praise her calmly and smile so that you do not interrupt her thought process—don’t forget that overexcitement can completely distract a dog from the lesson. Then calmly praise her again when she is down. Repeat the gesture with the body language and combining it with the command; then, if you want to use words alone, gradually phase out the body language.

“If she does not go down,” Martin suggests, “use your fingers on her back or the gentle leash movement down to follow through and ensure that she does. Once she is down, put your foot or hand [if you are kneeling] on the leash so she cannot get up and then sit down and spend some time with her. If she attempts to get up, just stay there and let her readjust her position so her down feels comfortable.”

THE DOWN: USE BEDTIME TO CAPTURE THE BEHAVIOR

Another way to reinforce the “down” command is to capture the behavior at bedtime. Take your dog to her bed or to the place in which she most often lies down at the end of the day. Tell her, “Bed,” or “Place,” or use whatever word or sound or gesture you want her to associate with lying quietly at rest. Then wait until she is beginning to lie down and use the command for “down” when she does. Repeat this a few times, and in a short time she will learn to go to her bed and lie down at your request.

Down is not a very exciting movement, but if you make it fun and put some excitement in your voice as your dog is moving, and follow up with a reward such as a ball or treat, then the game does become fun, and your dog will often go down quicker and more happily.

THE DOWN: TEACHING DOWN WITH A CLICKER

When teaching the down with a clicker as an aid, Kirk Turner stresses that, as with any other method, you’ve got to have patience to get the behavior you want from your dog. “I just wait. And wait some more. Eventually Sparky is going to lie down. All dogs do. They know how. Sparky wants my attention, but I am not looking at him or talking. Sparky is getting bored now. So he just lies down and … Click! Treat! Ignore. Pretty soon he is lying down all over the place where he knows I will see him. Now is the time to bring in the word down as I can predict he will do it anyway. Within a few minutes, I can say the word, and he will do the behavior three times for every one time he gets a click and a treat.”

THE STAY

The joint headquarters of my Dog Whisperer production company, MPH Entertainment, and my own business, Cesar Millan Inc., is a dog-friendly office. Any dog that is balanced, sociable, and well behaved is welcome, as long as the owner registers his or her dog and agrees to pay a $25 cleaning fee if there is an “accident.” As a result, our workplace is a joyous, dog-filled environment with anywhere from six to a dozen pets on the property at any one time.