In This Chapter

- Tackling multiple obstacles in the right order

- Becoming an effective course director

- Finding solutions to specific problems

In this chapter you find out

about these moves and how to teach your dog to sequence up to 20 obstacles in a

row. No joke! Working piece-by-piece, slowly and steadily, you’ll be out there directing

your superstar athlete who’ll look to you with eagerness and respect . . . and

before you know it, people will look to you with awe and envy, thinking “What a

harmonious pair!”

Before we finish, we troubleshoot

problems that befall many newbie handlers. The good news/bad news here is that

most problems result from human misjudgment and handling errors. But human

errors are way easier to correct than dog-related issues, so don’t fear your

missteps!

Mixing Obstacles

Envision a competitive agility

course — 16 to 20 obstacles laid out and prearranged in various positions and

angles on the field. There’s one starting point and one finish line. You and

your dog come out together, focused on

Eventually, your dog — yes, your

dog — will move seamlessly through a course of up to 20 obstacles. But don’t

get overwhelmed; it’s a building process, and what seems far-fetched now will

come together over time. Eventually, you’ll move from the starting gate to the

finish line in under three minutes.

Initially, you combine two or

three obstacles your dog has mastered. Begin with two or three jumps in a

straight line. As your dog masters the straight sequence, angle them in a

slight curve. Then add a tunnel. Then a well-honed contact obstacle. Slowly

chain more and more obstacles together and vary the positioning as you learn

different directing moves. For instance, you may start with two jumps, and then

toss in a third — or maybe a tunnel or contact obstacle — increasing the number

of obstacles in your sequence.

At some point, you can set up

your own mini-course. Please don’t wing this, especially if your aim is

competition. Figure out sequencing with the help of your agility teacher before

you try it at home. Bad habits are hard to break — no matter how many legs you

stand on!

Tip

You can visit the Agility Course Maps Web site (agilitycoursemaps.com/CourseMap.aspx) to see a few official sample courses that you can try after you know how to signal and direct your dog from one obstacle to the next. Look for a Novice or Starters level course — it may not be on the first page.

Tip

To figure out the spacing of the obstacles, speak to a professional. The distances between obstacles and the heights and measurements of the equipment are determined in large part by the size and breed of your dog.

Obstacle spacing is crucial when

sequencing a course. If obstacles are bunched, there will be little flow

because much of the dog’s concentration will be wrapped around gauging his

speed and approach. Spread them out and time will be lost racing back and

forth, not to mention the dogs who can quickly outrun their handlers!

When setting up a practice

course, there are a few general rules of thumb. The obstacles should be placed

so that the dog has 18 to 21 inches of straight runway to approach all jumping,

tire, or spread jumps; when a contact obstacle is presented, the dog should be

directed to approach the plank straight on. When angles are added to the course

layout, there needs to be a greater distance allotment to allow the dog to

direct himself to the next obstacle. There are programs available online that

allow you to design a course tailored for the coordinates of your location and

the measurements of your dog. My favorite is Clean Run Course Designer 3, which

you can explore at www.coursedesigner.com/newcd3;jsessionid=2B356C4442826D69A48A4093E100873F.

Directing Your Dog to Do a Sequence of Obstacles

When your dog is eager to

practice, reliably consistent in completing an obstacle, and responsive to your

directions, you’re ready to begin sequencing, arranging more than one

obstacle and directing your dog in a pre-determined order. There are two

parts to this process:

- Teaching your dog to perform a series of obstacles, arranged in various fashions

- Learning how to direct your dog and choreograph your motions to minimize your footwork and maximize your dog’s speed

Tip

When you begin sequencing obstacles together, include only those that your dog loves on a standalone basis. If he’s having trouble with one, for example, the dog walk, you may begin some sequencing moves that exclude the dog walk as you continue to practice this obstacle individually. Remember, your dog’s success is based on two things: his understanding of each obstacle and your proficiency in giving him clear, understandable directions.

Giving commands and hand signals

If you’ve trained your dog in

obedience, check your inner drill sergeant at the door. Many of the

tried-and-true obedience rules — use commands only once, keep your praise calm

or you’ll excite your dog, always work your dog on your left side — simply don’t

apply to this sport. On the agility field, you’ll likely find yourself

shouting. Excitedly, eagerly! You’ll often repeat commands as you urge your dog

through the course. Don’t worry, you’re not making mistakes! You’re simply

reflecting the nature of the game — and your verbal encouragement should bring

on a canine-adrenaline rush.

When I trained in agility, I

liked to think of myself as an ocean current — urging my dog’s enthusiasm with

words and motions to help her navigate the way. I knew she was excitable and

athletic, and her focus was drawn in 15 directions all at once. It was up to me

to keep her attention, to be the powerful current, so she would stay focused

and ride the wave!

When you’re out there, you have

two tools at your disposal to steady your dog and direct his way: commands and

body signals. Use both simultaneously, focus on your timing, and watch your dog

looking to you to light his way. Here’s how to use these tools:

- Loud, excited, urgent commands: As you navigate your dog around an agility course, give your directional commands with urgency and joy! Work on clear comprehension and directing body signals so your dog gets the visual on first command — think of your directions as a steering wheel that will . . . eventually . . . guide your dog across an ever-changing course configuration.

Remember

Always remember that you won’t be penalized for repeating your command should you need to do so. Agility is very different from everyday life, so say your directions loudly, repeat yourself if necessary, and urge your dog with an excited tone!

- Big body signals: When you want to send your dog off in one direction or another, don’t use a subtle hand gesture — use your whole arm as though it has the power to push your dog in the right direction. Bowling signals — large, theatrical, bowling-like arm sweeps — should be used to direct your dog every path of the way. When you want your dog to race to an obstacle, don’t walk toward it; run fast and keep your eyes fixed on where he should go as you lean toward the obstacle with your whole torso and wave your arms to urge his excitement!

Tip

When signaling, use the arm or hand closest to the obstacles.

Remember

Commands and signals work in tandem. Your dog listens for your directions — and is powerfully swayed by your encouragement — but he depends on your signals to help him make split-second directional decisions. Think electricity here — the more animation you put out, the higher the voltage. Your dog responds to whatever you send out, so ramp it up!

Getting a handle on handling

While your dog may be eager to

learn sequencing, it’s up to you to simplify it. No matter how well he knows

each individual obstacle, the new, multi-obstacle configurations will be

something completely new — and your dog will be clueless.

Did you think you’d just wing it,

running around the course telling your dog which way to go? The problem is that

your dog can outpace you in a nanosecond, and if he loses sight of you, he’ll

stop in his tracks, utterly bewildered yet still pulsing with adrenaline — a

tough combination. That’s why learning to direct him with verbal and body cues

is important.

Tip

Before you teach your dog how to move about an agility course, study and learn the human moves. Study the commands. See how they differ between the way you use them with your dog in your routine life and the way they’re used to direct your dog’s placement on the course. Once you see the science that belies the chaos, you’ll feel more confident directing your dog.

Fortunately, there are fine-tuned “human” techniques for sequencing agility obstacles, and I cover them here. Take time to envision, learn, and practice them (when possible without your dog and in front of an experienced handler) before you begin! Once you embrace the integral role you’ll play on the field and feel comfortable with

the commands and body cues, you’re ready to work with, teach, and direct your

dog.

Teaching “Here”

“Here” is similar to the “Come”

command — it tells your dog to run toward you. The difference? “Come” invites a

reconnection — a stop-and-share-the-moment. Agility requires top speed — so “Come”

isn’t the ideal choice.

On the course, “Here” directs

your dog toward you — then you need to quickly send him to the next obstacle,

for example, “Tire” or “Frame.” Practice your timing — shouting and signaling

to the next obstacle before your dog reaches you. Invigorating!

“Here” should alert your dog to

turn quickly in your direction. Wave a toy or a cup of treats, and shout “Here”

as you step back away from your dog or call to him from a distance. As he runs

in your direction, toss the object in one direction or the other shouting “Go

left” or “Go right” as you do.

Getting your dog to lead out

Okay, I’m going to state the

obvious. You have two legs; your dog has four. No matter his size, he’ll

outpace you. Rather than slowing his progression, teach him to lead out —

to race ahead of you and take whatever obstacle you point him toward.

Tip

Most people tell their dogs to “Get out” or “Go on.” Use one command consistently, and practice the playful exercises found in Chapter Laying the Foundations for Agility. Taught properly, your dog will grow confident racing ahead of you.

The “Get out” command rarely

stands alone. Once you teach your dog to race ahead of you, you need to

incorporate directions that send him toward the next obstacle. Use your

dramatic bowling body signals to point to the chosen obstacle and a verbal cue

to further specify it, for example, “Get out–Tire!”

Technical Stuff

The command “Get out” has a lot of uses on the agility field. Once your dog has mastered his obstacles and is eager to perform them, you may notice that you’re holding him back . . . it’s the two-leg to four-leg ratio. If your dog is outpacing you on the way to an obstacle, you can use “Get out” to support his initiative and vision. In competitions, you’ll likely use this move at the very end of the course, sending your dog out to take the last series of obstacles and cross the finish line solo.

Using call-offs

Call-offs are used on-course to

call a dog away from an incorrect obstacle. You may call out the name of the

proper obstacle, “Go left or “Go right,” or “Here” if you’re well positioned to

bring the dog toward the right one. Envision your dog running a course of

preset obstacles. As he finishes one obstacle, he has two choices: run straight

and take the obstacle that faces

While these maneuvers are

generally used in higher-level competition, they sharpen even a novice dog’s

concentration.

“Go left,” “Go right”

While this may sound like an

exercise for the trick chapters, your dog can learn his left from his right —

and you can use these commands to direct him on the field.

In Chapter Introducing

Your Dog to Jumps, Tunnels, and Tables, I introduce you to

a fun game, tossing rewards to either side and routinely shouting out the

appropriate cue. The following exercise challenges your dog’s comprehension:

1. Set up two low jumps side

by side.

2. Walk out beyond the jumps

15–20 feet, while leaving your dog in a “Sit–Stay” facing the jumps.

3. Stand in the center of the

two jumps.

4. Command “Here–Left,” as you

dramatically signal with your left arm and run across to the middle of the left

jump.

If necessary, use a helper to guide your dog.

5. Now practice “Here–right,”

reversing your directional cues.

When you’re working a course, use

the commands “Go left” and “Go right” to help your dog navigate the obstacles,

especially when the layout is tight and confusing.

Warning!

Traps are never a good thing. An agility trap is set by positioning the exit of one obstacle in line with the entry of another but requiring the dog to completely avoid it. It’s the handler’s job to call his or her dog off-course and direct the dog to another, often less-obvious obstacle. A common trap involves the tunnel placed directly under the A-frame: Because the tunnel is a hard obstacle to avoid anyway, the temptation is compounded! Traps are usually found in higher-level competitions — but practice them early, just in case one crops up sooner than you expect.

Footwork on the field

When working a sequenced course,

your dog’s success or failure often depends on your footwork, steadiness, and

clarity. If you mix up your signals or blurt out the wrong direction, you dog

won’t know what to do — he’ll simply respond. This blind devotion can result in

a missed obstacle or a dog who’s off-course and/or out of sync. Before you get

nervous, a quick review is in order — knowledge is power, no matter what your

activity!

Deciding where to position yourself

As you direct your dog, you want

to position yourself to minimize your mobility (too much activity disorients

your dog) while staying visible to your dog as he maneuvers each obstacle.

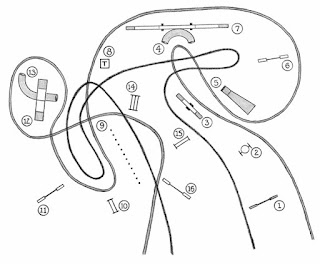

Check out Figure 15-1. Identify

the inside line or center footprint of the course versus the outside

line, the course path that encircles all the equipment. The inside line

keeps you on the inside path of the obstacles so you can direct your dog like

the arms of a clock. The outside line puts you outside of the center, or on the

periphery of the course. In trials, you’ll have time to walk the course ahead of

time to determine the best path for directing your dog during a competitive

run.

If your dog will “Stay” at the

starting line, you can walk out and stand right next to the first set of

obstacles. In this instance, you can call your dog right to you using the “Here”

command.

As your dog is running forward,

position yourself to direct him to the next obstacle. If you’re able to stand

next to a jump, for example, you can shout “Here–Over” to signal the jump. If

the tunnel is next, you can just shout “Tunnel” as your dog clears the

obstacle. With agility, you never know what configuration you’ll get, but you’ll

have fun piecing it all together.

Tip

Practice your timing: As your dog is taking the preceding obstacle, move toward the next obstacle and command the next move. No time for a hug!

Working on both sides

At home, my dog Shayna always

followed on my left side. When she approached me on the couch it was always to

my left. When practicing tricks, she skewed her posture to the . . . you guessed

it . . . left. But on an agility field, she would work on either side of me. As

we moved quickly around the course, I would sometimes be in front of or behind

her, often maneuvering my position to the left or right depending on the path

of the prearranged course. As both of us moved through the obstacles, my

positioning helped her orient her next move. From her perspective, my

positioning was unpredictable, but watching me would help her orient herself on

the course.

Tip

Throughout the learning phase, mix it up: Stand both to the right and left side of an obstacle. Use your vocal cues and body signals to guide your dog from one obstacle to the next.

Crossing your dog’s path

As you learn to handle more

obstacles, you may see a course configuration that shifts the inside line. To

make the most of your footwork, you may need to cross your dog’s path in order

to direct him to the next move. Here’s how crosses work:

- Crossover (cross-in-front): If you need to cross in front of your dog, the only thing to practice is timing. If you’re too late, you may ram into your dog or pull his attention away from the next obstacle in the progression.

Tip

Study each course before running it with your dog. When you determine a crossover is the best move — perhaps the tunnel is curved away from the center and upon exiting your dog will need to change direction, or the jump/contact obstacles are lined up so that your dog will have to turn off the center line to take it — envision making the cross the moment your dog has committed to the preceding obstacle, but long before he’s completed it. Of course we’re talking about milliseconds; nevertheless, cross early and cross quickly. Call out the next direction as your dog completes each obstacle — he won’t skip a beat!

- Cross behind: Some courses change their inside lines in other directions that necessitate a cross behind. Here you would cross behind your dog as he took an obstacle in order to position yourself to direct his next movement. This would be a good move when your dog must turn 180 degrees to move to the next obstacle. The tunnel is the ideal obstacle with which to make this shift because it gives you that extra millisecond to make your shift, though you may need to make this move elsewhere as well. Similar to crossovers, steady your timing. Once your dog has committed to the obstacle in front of him, make your cross. Shout your next direction as your dog completes the obstacle and make sure he can find you the instant he reorients himself on the field.

Troubleshooting

Believe it or not, the hardest

thing to manage on an agility field isn’t your dog . . . it’s yourself: your

handling techniques, your footwork, and your temper. You’ll have good days and

not-so-good days. Like you, your dog will also have on days and off days — days

he’ll be steaming up the car windows and days he’d probably rather hang out at

home. But the difference between you and your dog is that you can articulate

your feelings. You can pop a couple of aspirin and call off the show when you’re

feeling under the weather. Your dog can’t tell anyone anything — it’s up to you

to know your dog, to “listen” to him, to dissect his behavior, and to trace any

inconsistencies to their root causes.

In this section, you discover how

to read your dog’s physical discomfort signs as well as how to troubleshoot

problems like missed contacts and incomplete jumps. You also learn to take an

up-close look at yourself to discover if, by chance, your handling is creating

confusion. Many times it’s important to ask what you’re doing wrong!

Respecting your dog’s physical inhibitions

If your dog is having trouble on

the agility course, physical limitations are some of the first things to watch

for. In this section, I discuss illness and injury as well as breed

limitations, whether they’re related to your dog’s body shape or demeanor.

Watching out for illness and injury

Think of the last time you had an ache or a pain . . . perhaps it was that awkward misstep that tweaked your ankle, something you ate, or a sporty excursion that left you zapped of your normal get-up-and-go. You can’t control everything; like everyone else, you learn to roll with the punches. Well, your dog is no different: He’s not a machine. Trapped in his mammalian frame, his body can and often does suffer similar shutdowns.

Learn to read your dog — watch

his movements, expressions, and behavior. If he’s having an off day, consider

why.

Tip

Take some time to know your dog. Watch him on his best day. Look at how he moves; count his strides as he approaches the single-bar jump; note the happy gleam in his eye as he watches you for his next cue. Record these moments in your head for comparison purposes. Also take his resting temperature, and pass your hands along his legs, hips, and joints. Notice how he reacts to your touch.

If you suspect injury or illness,

caress your dog, speak to him calmly, and slow down. If you push him through or

force him to practice, you may damage his enthusiasm for the sport, and thus

your agility career. In my mind, it just isn’t worth it. Treat your dog as you’d

like to be treated.

Warning!

Many injuries and illnesses require a veterinarian’s attention. Reference Chapter Top Ten Sports Injuries for Dogs for physical conditions, and note those that do.

Recognizing breed limits

More dogs can think like a Border

Collie than move like one. No matter how eager your dog is to do agility,

respect his breed restrictions (see Chapter Considering

Agility Training). Place obstacles at heights and

angles that limit joint stress and maximize your dog’s success rate.

If your dog is refusing ramps,

balking at jump heights, or refusing to follow your lead, consider the obstacle’s

position: Has it changed or been raised? Your dog’s physical stature dictates

how obstacles are set for repetitive practice.

Next consider your training

approach. Some dog breeds, such as the Border Collie, the Australian Shepherd,

and the Golden Retriever, thrive on repetition. These breeds have their own

inner dictator pushing them to strive for perfection. Repetitive practice helps

them to nail a performance strategy.

Other breeds are not bred for

repetitive work, including many instinctively driven breeds like Terriers,

Nordic breeds, and Hounds. These dogs snub routine practice. When working them,

the best reward for a breakthrough performance is a few days practice-free.

They seem to encode success better when they’re allowed to sleep on it!

Handling the dog who acts up

My daughter’s a ham. She’s

delightful, funny, and loves a big audience. Why talk when you can shout? Why

stand when you can dance? Why sit still when you can make a funny face and

scratch your dog’s head with your big toe?

Dogs have personalities, too.

Many of the dogs who act up are comics: smart, energetic dogs that dance on the

edge of good behavior. These dogs

Tip

So how can you manage your comedian? Try the French-fry cure. Find an über-treat that your little jokester will do back flips for: a mind-bending reward that he only gets on special days. Use your chosen tidbit to keep his attention: He’ll soon learn to focus on you no matter what the distractions.

Treat rewards are allowed during

practice runs and match competitions. Though you can’t reward your dog in the

midst of a trial run, you can certainly give him a jackpot at the end!

If your dog acts up and you’re

left empty-handed, remember that a dog who acts up is still a little stressed.

While having all eyes on you is a bit of a thrill, it can be jarring! Though he

looks like the life of the party, he’s jumbled up inside. Stay calm and

remember these cardinal rules:

- Don’t look at him. Any attention — negative or positive — will egg him on. Let him freak out and keep a watch out of the corner of your eye, but don’t shout or track his movements.

- When your dog calms down, sit down and tie your shoe (or pretend to). If he’s still wary of you, try the “Ouch — I’m really injured” move. Shriek like you’ve been shot. When he looks to see what happened, fall on the ground and clutch your leg in pain. When he runs over, calmly reach up and grasp his collar; then put his leash on and walk off the course. Keep your cool, lower your head, and look at the ground. Don’t reconnect or let him have anyone’s attention for at least five minutes: No attention or treats for that performance.

Warning!

Of all the things that can happen during a trial, having your dog go wild is perhaps the most embarrassing. While controlling one’s temper is a tall order, lashing out at a dog only guarantees more stress and an inhibited agility performance.

Fixing obstacle errors

Your dog may be having trouble

with the obstacles — flying past the contact zones, refusing to do an obstacle,

knocking down bars on the jumps, or choosing to do an obstacle out of order. In

this section, you find out how to get your dog back on track.

Missing contacts

Some dogs dream of flying.

Fast-paced and excitable, these dogs love a sequenced course and race to beat

the clock. Contact zones — on the A-frame, dog walk, and teeter obstacles —

slow them down. While the mindfulness

Tip

If you’re having trouble, try teaching your dog a cue word during your practice runs: a word you can repeat during trials, such as “Easy.” This word can help remind your dog to slow down just enough to nail his targets!

Refusing an obstacle

Dogs always have a perfectly good

reason for refusing an obstacle. If only they could speak! The most common

refusals happen when

- A dog is sick or injured.

- He doesn’t have enough runway space.

- The obstacle is raised too high.

- The signals or directions are unclear.

- He makes an unsteady entry onto a ramp or tunnel.

He’s momentarily confused as to

which obstacle to take.

Many of these faux pas are

handler’s errors, and this is good news. If you’re having these issues, look at

how you can change. No one can learn these steps overnight — it took me a long

while! Find a master to watch and critique you. Listen and learn — your dog

will be so glad you did!

Double check to ensure your dog

is in good physical condition and the obstacles are set to ensure his success:

Nothing is more frustrating for dogs than being pushed beyond their limits.

They want a clear run too!

Knocking down bars

Dogs can get in a bad habit of

knocking down bars as they clear jumps. Some nick the bar with their hind legs,

often not even realizing what they’ve done. Other dogs push off with their hind

legs or bump the bar on the way up. What to do?

First, stay calm when it happens.

If you rush in and give your dog attention — negative or positive — he’ll often

do it again just to get you to come near him. Retrieve your dog, review the

jumping section in Chapter Introducing

Your Dog to Jumps, Tunnels, and Tables, and follow these tips:

- Consider your practice jumping height. While you don’t want to work at competitive heights full time, it’s important that your dog be able to clear this height reliably. Set the jump to this height every fifth run to ensure your dog can clear it.

- If your dog is oblivious to the fact that the bar is coming down, check the bar itself. Is it made of lightweight plastic? Fill the bar with sand, and plug the ends of it. If it’s already weighty, toss some screws in a soda can and tie it to the end of the bar. When your dog hits it, he’ll know.

- Each time your dog knocks down a bar, ignore the mistake and set your sights on teaching him a better approach. Set the bar low to encourage full clearance, and reward him like a newbie. The contrast will make it clear. Slowly raise the bar to its appropriate height.

Going off-course

A dog is off-course when he takes

an obstacle out of sequence or takes one that’s not included in the course. When

this happens, always stay calm. Consider whether your dog is mature enough to

run a sequence.

Another mistake that can lead to

an off-course reaction is a habit that’s created during practice runs — when a

handler either calls or sends his or her dog back over a missed obstacle.

Always approach obstacles from a predetermined direction. If your dog misses an

obstacle, step away and call him to your side. Take him back and start from the

top.

Reining yourself in

Sometimes, you just have to let

your dog go — to run the course, that is. Playing the role of an overbearing

parent causes your dog to become too dependent on you, and it can get you and

your dog disqualified in competition. In this section, I discuss problems with

guiding your dog too closely.

Overhandling

Overhandling is a term

used in competition where the handler uses his or her body or voice to

over-direct a dog or to prevent the dog from making a directional mistake.

Often when dogs are first learning how to sequence a series of obstacles, a

leash is needed to guide them through the equipment. Initial off-leash

maneuvers often involve physical direction too. Hands are used to manipulate

motions, spot efforts, and reassure insecure dogs. Praise and rewards are doled

out on a regular basis.

This newbie involvement can lead

to interactive dependency and insecurities if overused. When dogs aren’t weaned

from this constant reassurance, solo performances can be hard for them to

manage.

In competitions, overhandling may lead to disqualification. Constant interference or a dog’s overdependence on your guidance conveys to all spectators that you aren’t quite ready for this challenge. Don’t push yourself; don’t pressure your dog. Review the weaning steps in Chapters Introducing

Your Dog to Jumps, Tunnels, and Tables and Teaching

the A-Frame, Dog Walk, Teeter, and Weave Poles to ready yourself for a complete course run-through.

Blocking

To envision a blocking move,

imagine a dog racing out of the tunnel and having two equally distant obstacle

choices. Instead of guiding him with a command or signal, the handler simply

stands in front of the off-obstacle’s entry path. That’s blocking — it’s

fudging with a capital “F.”

Blocking is another form of

overinteraction. Though slightly more subtle than overhandling, no one can fool

a judge. If practiced too often, a dog will grow mindfully aware of the body

position of his handler and use it to determine his course.

by Sarah Hodgson

ReplyDeleteWell written articles like yours renews my faith in today's writers. The article is very informative. Thanks for sharing such beautiful information.

Knowmydog

Best Dog Food for PUGS

Best Dog Foods for Schnauzer

Best Dog Leashes for Running

Best dog foods for diabetic dogs

Best dog foods for border collies

Best dog food for dobermans

Best dog foods pitbulls

which dog breed is best

How many dog biscuits per day

How much dog food to feed my puppy

What dog eats the most

which dog is banned in india

which dog is best for beginners